↧

Tour de blogosphere: a profile on me now online at Apartment613

↧

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Dan Thomas-Glass

Dan Thomas-Glassis the author of The Great American Beatjack Volume I (Perfect Lovers Press), Kate & Sonia (in the months before our second daughter's birth) (Little Red Leaves' Textile Series), Seaming (Furniture Press), and 880 (Deep Oakland Editions). He works as a middle school teacher and administrator, and lives with his wife Kate and their daughters Sonia and Alma in California.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Well... I'm not sure I've published a book, exactly. I've published a photo-essay-poem on a freeway, a single-poem pamphlet, a textile chapbook, and a collection of record-poems. I'm hoping to publish an actual book-shaped collection soon. What I can say is that the process of writing and rewriting a book ms has been hugely informative: it has brought my attention, ideas, and investments into sharper focus.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Walt Whitman, more or less. In 10th grade we read various parts of Leaves of Grass and it exploded a lot of things for me. I started writing feverishly, in every shape and direction I could find. I was very spongy for a long time—I tried on vispo forms, performative work, narrative, just whatever. I've often worried that I'm too omnivorous, in that way. But lately I've stopped worrying, and just let myself write.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I write a lot, and quickly. I revise a lot as well, but also quickly. I try to listen for language, then write what I hear. I'm very ear driven—a lot of the drafting process is about sound. And then the revision is often about form. Frequently I forget to think about content—about what I'm writing about. Usually I figure that out after the fact, or not at all.

It is also true that sometimes the form comes first, and those poems tend to have a different arc, and move more slowly. Some projects (like the Beatjack) are slower just because of the formal work of scanning poems and then writing into those stolen meters.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I don't work on a book, no. I write in seasons—I've had poems organized in files on my computer by season (Fall 2012, Winter 2013, Spring 2013, etc.) for about a decade. Those seasons often collate questions, experiences, explorations for me.

Lately poems begin with being a parent, and extend to what intrudes on daily life—anything from drones to economic collapse, occupy, television, music (a lot of music), work, dead loved ones, whatever.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I like readings because they bring writing into a kind of social contact that is different from other less physical forms like email or facebook. That is often generative. I try and bring my daughters, but often the time doesn't work—they're usually in bed by 8pm.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

How to put the blooming optimism of being a parent to two brilliant & loving daughters into conversation with the crushing horror and enduring pessimism of contemporary life.

But in a long spring poem I'm working on I just wrote

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

To love people, to help people, to make life better than it is, to find meaning, to care without shame, to seek the edges of systems, to slow down and observe, to be honest, to connect with ancestors and long histories, to create ritual, to imagine other possible worlds.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

When I list the editors who have helped bring my projects into the world, I am embarrassed at the riches I have enjoyed: Stephanie Young, Christophe Casamassima, Ash Smith and Dawn Pendergast, and Dana Ward. Essential doesn't even begin to touch their importance to my ongoing thinking.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Not exactly advice because it isn't written in the command form, but this quote is on our refrigerator (typed by my mom some once upon a time on an index card)—

"A hundred times every day I remind myself that my inner and outer life depends on the labors of other men, living and dead, and that I must exert myself in order to give in the measure as I have received and am still receiving." Albert Einstein. That is the short version the internet here at work is offering me. The longer version, on our fridge, includes being drawn to the simple life, and notes that class difference is fundamentally based on violence.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

They are in different places in my brain. I write a lot in many forms for work and life—those are all often similar, and poetry is distinct from them in that it leads me more than I lead it.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

My day begins when either Sonia or Alma wakes up. Sonia usually yells for me, and Alma usually yells for Kate. We make coffee, eat, get dressed. Go to work. Sometimes when I bike to work I hear poems. Sometimes I write them down when I arrive. But being a writer who is also a parent and with a very full-time job that is not about writing per se, my routines are not centered on writing. I write when I can steal the time to write.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Some seasons and some years I write more than others. I've never worried about stalling.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Jasmine, ocean, eucalyptus, that big-street smell of lots of cars and corner stores.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Music. Lots of music. But pretty much anything. I read a lot, and most of what I read influences what I write in some way or another.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Dana Ward's prose turn in his poetry since Typing Wild Speech has been hugely important for me. Brenda Hillman's poetry, its attention to landscape. Roberto Bolano's playfulness in history. Ash Smith and Anne Boyer's recent writing and thinking about domesticity and parenting in poetry, some of which is about returning to Bernadette Mayer's work. There are so many, really—isn't that what being a writer is about, reading too much?

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Visit New Orleans.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I love cooking Mexican food.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I don't know. I was drawn to words, as far back as I can remember.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I read too many books, many of which are great, to pick just one. I never watch movies though, so that's easy—the only movie we went to last year was Beast of the Southern Wild, and I cried. It was beautiful.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Books—Daughters of your century is a complete manuscript, and then there's another book about daughters.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Well... I'm not sure I've published a book, exactly. I've published a photo-essay-poem on a freeway, a single-poem pamphlet, a textile chapbook, and a collection of record-poems. I'm hoping to publish an actual book-shaped collection soon. What I can say is that the process of writing and rewriting a book ms has been hugely informative: it has brought my attention, ideas, and investments into sharper focus.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Walt Whitman, more or less. In 10th grade we read various parts of Leaves of Grass and it exploded a lot of things for me. I started writing feverishly, in every shape and direction I could find. I was very spongy for a long time—I tried on vispo forms, performative work, narrative, just whatever. I've often worried that I'm too omnivorous, in that way. But lately I've stopped worrying, and just let myself write.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I write a lot, and quickly. I revise a lot as well, but also quickly. I try to listen for language, then write what I hear. I'm very ear driven—a lot of the drafting process is about sound. And then the revision is often about form. Frequently I forget to think about content—about what I'm writing about. Usually I figure that out after the fact, or not at all.

It is also true that sometimes the form comes first, and those poems tend to have a different arc, and move more slowly. Some projects (like the Beatjack) are slower just because of the formal work of scanning poems and then writing into those stolen meters.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I don't work on a book, no. I write in seasons—I've had poems organized in files on my computer by season (Fall 2012, Winter 2013, Spring 2013, etc.) for about a decade. Those seasons often collate questions, experiences, explorations for me.

Lately poems begin with being a parent, and extend to what intrudes on daily life—anything from drones to economic collapse, occupy, television, music (a lot of music), work, dead loved ones, whatever.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I like readings because they bring writing into a kind of social contact that is different from other less physical forms like email or facebook. That is often generative. I try and bring my daughters, but often the time doesn't work—they're usually in bed by 8pm.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

How to put the blooming optimism of being a parent to two brilliant & loving daughters into conversation with the crushing horror and enduring pessimism of contemporary life.

But in a long spring poem I'm working on I just wrote

I decided—and I believe that's true, or something I'm working toward, too.

on no theory

for these words

but what small

hours unmoored

in days

reveal.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

To love people, to help people, to make life better than it is, to find meaning, to care without shame, to seek the edges of systems, to slow down and observe, to be honest, to connect with ancestors and long histories, to create ritual, to imagine other possible worlds.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

When I list the editors who have helped bring my projects into the world, I am embarrassed at the riches I have enjoyed: Stephanie Young, Christophe Casamassima, Ash Smith and Dawn Pendergast, and Dana Ward. Essential doesn't even begin to touch their importance to my ongoing thinking.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Not exactly advice because it isn't written in the command form, but this quote is on our refrigerator (typed by my mom some once upon a time on an index card)—

"A hundred times every day I remind myself that my inner and outer life depends on the labors of other men, living and dead, and that I must exert myself in order to give in the measure as I have received and am still receiving." Albert Einstein. That is the short version the internet here at work is offering me. The longer version, on our fridge, includes being drawn to the simple life, and notes that class difference is fundamentally based on violence.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

They are in different places in my brain. I write a lot in many forms for work and life—those are all often similar, and poetry is distinct from them in that it leads me more than I lead it.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

My day begins when either Sonia or Alma wakes up. Sonia usually yells for me, and Alma usually yells for Kate. We make coffee, eat, get dressed. Go to work. Sometimes when I bike to work I hear poems. Sometimes I write them down when I arrive. But being a writer who is also a parent and with a very full-time job that is not about writing per se, my routines are not centered on writing. I write when I can steal the time to write.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Some seasons and some years I write more than others. I've never worried about stalling.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Jasmine, ocean, eucalyptus, that big-street smell of lots of cars and corner stores.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Music. Lots of music. But pretty much anything. I read a lot, and most of what I read influences what I write in some way or another.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Dana Ward's prose turn in his poetry since Typing Wild Speech has been hugely important for me. Brenda Hillman's poetry, its attention to landscape. Roberto Bolano's playfulness in history. Ash Smith and Anne Boyer's recent writing and thinking about domesticity and parenting in poetry, some of which is about returning to Bernadette Mayer's work. There are so many, really—isn't that what being a writer is about, reading too much?

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Visit New Orleans.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I love cooking Mexican food.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I don't know. I was drawn to words, as far back as I can remember.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I read too many books, many of which are great, to pick just one. I never watch movies though, so that's easy—the only movie we went to last year was Beast of the Southern Wild, and I cried. It was beautiful.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Books—Daughters of your century is a complete manuscript, and then there's another book about daughters.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

↧

↧

Handsome journal, volume 5, no 1

THE WORLD IS BEAUTIFUL BUT YOU ARE

NOT IN IT

Let me refer to myself in glorious ways:

colors seem brighter, the sky is a shocking blue.

I carry my stomach in this bowl

and earth is planted in my blood.

From your last letter, I gather hills.

I’m trying to keep my tenderness in check.

Trying to see what kind of grill the neighbors have

is everything I couldn’t do before.

Now brown eggs shift heavy in my palms, this bowl.

Words make their way up my thigh.

I swear very nice boy and I refer to myself.

No. The hills are holding you and I refer to myself.

Let’s be honest: I need a real man, I say out loud.

Every weakness I have settles into a tree trunk,

stays all winter. I don’t know if I mean it.

Winter has lasted five years already.

This morning I press into the edges of my stomach.

My mother makes coffee in California.

Ladies will say we are expert with machines

but they will be two bottles under sangria.

I said you could make music out of this.

Ingesting artificial palm trees, exploding.

Your letters are getting shorter. I am getting close

enough to the sun to touch the tip of its cigar.

We carry what is shocking and heavy in blood.

Music seems brighter: the sky the sky. (Morgan Parker)

After a short wait, I finally received my contributor copy of the fifth annual HANDSOME journal, produced by Black Ocean. Launched recently at AWP in Boston, this issue contains one hundred and twenty pages of strong writing, most by writers I haven’t previously heard of. I’m slowly and still working my way through learning the names and writing of contemporary American poets, but there are still only two that haunt the pages of this new issue, being Deborah Poe [author of a recent chapbook through above/ground press] and Brian Henry. A graceful journal of new poetry, HANDSOME is edited by Paige Ackerson-Kiely and Allison Titus, and published by Janaka Stucky. Another of a series of journals who publish work sans author biography, I’m left with the work itself, immediately struck by the work of Morgan Parker, Kristina Marie Darling and Sarah Goldstein. There is something of Jenny Boully’s The Body: An Essay (Slope Editions, 2002) to Kristina Marie Darling’s poem, in that the footnote quickly overtakes the body of the poem. Sarah Goldstein’s pieces in this issue are a small handful of “untitled” prose-poems, wrapping a rather straightforward lyric story with just a hint of something more, something surreal, akin to Miranda July or Lydia Davis. She says just enough in each piece, but there is so much more beneath the surface; suggested, but still hidden.

UNTITLED (PROPERTY)

The woman in the house down the road, whose phone bill you accidentally received and ripped open, fills her doorway, out of which wafts the dark smell of potpourri. You’ve seen her in the branches of the furious thickets between your houses calling her dog, thrashing like a shark in a net. You talk about the neighborhood squirrels: the big one with deep cuts on its shoulder, and the other one that made it through the winter without any fur. Large white cat in the window, large yellow dog pushing and whining behind her. “Oh, you’re so bad, you’re so bad,” she says to him. The dog always runs to you when he sees you, snapping the leash out of her hand, shoving his desperate head into your belly.

Some other pieces that struck include Jenny Drai’s poem “DER ABFLUG,” as well as Audrey Walls’ striking poem “Aquaphobia,” which ends with the lines: “You could drown in two inches // of water, my mother once warned. All you need / is someone to hold you under.” Kerri Webster has four poems in the new issue, each with the title “DIADEM,” and I wonder if these are a stand-alone quartet, or, like Noah Eli Gordon’s The Source (New York NY: Futurepoem Books, 2011), part of something much larger? I would like to see more.

DIADEM

Jupiter is fucking with me. What I know

of cruelty: a world is made

we did not ask for. In the dark, boys

set the dog on fire, let it loose

in the field. What

do you believe? Chanting what

as you go to sleep? I

see: same trees. Same locust

blossoms. I walk and walk. Smoke

from the burning scrapwood

shuts my eyes.

↧

Noah Eli Gordon, The Year of the Rooster

OBLITERATING HISTORY IN THE PLEASURE OF HOLDING FORTH

A first line is reason enough for a second, for a segment, unisexual & solitary as an organ. Our doctor operates a mechanism & calls it anatomy. Our dancer operates in music, which is the same. Whorled, lance-shaped leaves smear the window. Windy instrument, windy agency. Active principles everywhere

charging inertia. Syntactic propositions rest a harmonious unified totality on a reupholstered couch. Smash the shell to bits & hear the ocean in this lime.

As the author tells us in the book’s acknowledgments, the poems in Noah Eli Gordon’s The Year of the Rooster(Boise ID: Ahsahta Press, 2013) were “composed and revised between 2004 and 2012.” Composed with bookending prose-poems sections, the core of the collection is the seventy-one page collage-poem “The Year of the Rooster,” named for the tenth of a twelve-year cycle of animals in the Chinese zodiac, alongside a shorter piece, the sprawling twelve-page “The Next Year: Did You Drop This Word.” Through the four sections, the collection works from precision to collage to excess to precision.

Merged with a cycle of five elements, the most recent cycle of the Chinese Year of the Rooster, February 9, 2005 – January 28, 2006, was known as the “wood rooster.” Those born during the Year of the Rooster are said to be brave, romantic, motivated, proud, blunt, resentful and boastful. The title section that centres Gordon’s newest poetry collection is composed as part dream, part admonition and part letter, with some sections written as a series of journal entries, directed at “Roo,” as though attempting a map in which to find direction. Some parts are even written as a series of chants, citing repeating rhythms and phrases, making parts of this collection as much for the ear as for the eye. Composed in so many directions, the title section writes across an enormously large canvas, one contained only by the bookended prose sections, holding together what otherwise might be unwieldy.

What a rooster is

stubborn alienation

fertile adornment

a common weather vane’s

most compatible match

steady indication

of which way

winds are blowing

distinctive double squawk

muffled wing beats

O my lord, revered priest, devotee

brave shame brooding

all my erect ones

how many kids

equal a kingdom

not present

a hen takes the role

stops laying

& begins to crow

O my lord, revered priest, devotee

what a rooster is

blah, blah, blah, the body

There are elements of Gordon’s previous works that explore the emergence of patterns and repetition, such as his poetry collection The Source (New York NY: Futurepoem Books, 2011) and current work-in-progress, “The Problem,” both of which are constructed out of poems each with the same title. Through the repetitions emerge the small differences, the distinctions akin to a series of daily photographs taken from the same spot. In The Year of the Rooster, the repetitions aren’t so obvious, but the poem wraps around a central core, a centre, the foundational image of the Year, the “Roo,” and the polyphonic nature of multiple voices, of which the author is but one: “You & Roo’s collaborative poem / on the ills of capital / You & Roo’s condemnation of nudity / with all clothes removed // Blah, blah, blah… the body, etcetera” (p 45).

You have something to say, why not say it?

It’s nothing

They gave me a trumpet & I think of the movies

& loneliness like a bottled-up doubt

Ice on the lake

Did you mean lacking?

I’m not talking I am

After details, everything quaking

A history (if that’s the word) being opened

You don’t share a house you share

rooms, feathers, an even memory’s wake-up call

It’s stagnant

but the Rooster’s a trope, regal

without subordination & attendant baggage

Even wasps have feathers

No, too skinny

Everything skinny is ominous

↧

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Paula Eisenstein

Paula Eisenstein writes and commutes in Toronto. Her first novel Flip Turn is a Stuart Ross book. It came out November 2012 from Mansfield Press. Paula has been diligently filling her writer credential card with recent publications in Descant and the anthology The White Collar Book. Upcoming you will find her work in filling Station and for a toonie purchase one of her poems at a Toronto Poetry Vendors vending machine. Paula has been a contributing editor at Influencysalon.ca.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book Flip Turn just came out this past November. Being in the state of waiting and wanting to find a publisher and have Flip Turn published and to be recognized as a real bona fide writer is done with. Now that it has happened, I’m published, I’m a “for real” writer, I want more. I am less willing to put up with putting off writing. I’m meaner and crankier.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

At this point in time, I don’t relate very well to those different categories. I think how I write is a blend. I do like to write from my experience, but my experience is tenuous. It is uncertain. I am uncertain. I do like strong form though what I see as strong form others don’t necessarily.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

The method that worked well for me writing Flip Turn was quickly jotting down the structuring ideas that were coming to me, in point form. Then I would fill in, or write to those different overview or structuring points. The structure wasn’t necessarily linear but to my mind formed a larger connecting/disconnected narrative. There are also times I can just go on a long writing jag and the writing will circle back the way I need it to, or it needs to, but other times I am aware I have lost track of parts.

Often just getting anything down is fine. Sometimes what I start out with doesn’t change that much, other times it morphs into something completely different.

4 - Where does fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

With Flip Turn I intended for it to be an extended narrative or book. I had an idea of beginning, in betweenness and end. The intention was similar with The Pinery Trip, a (yet unpublished) project I collaborated on with my husband (artist Larry Eisenstein), made up of pairings of his drawings with my writing. While Pinery has narrative components it’s not an extended narrative, it reads more like a book of poetry. But, again, the plan was for it to be a theme based book. I do too write little solo vignettes not intended to be part of a larger project. Or maybe they’ve just never found their sister and brother parts to make them part of something bigger. I’m working on something now, small pieces, based on a theme. Overall, at this time, I do like having a larger framework to work within.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I don’t have a lot of experience giving readings yet. I’ve given some readings that I think went beautifully, that I enjoyed and felt the audience connected to. I’ve given others I have been disappointed in. I think the strength of my reading can have some influence over the audience reception. But there is also a degree of the intangible in the audience. Maybe I should try to think of that as something that could be fun.

I have a reading upcoming next week at which I hope to simply experience whatever the audience response is, to allow getting a feeling back or another take on what my writing is about, rather than pushing for a specific response.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I wrote Flip Turn in something of a vacuum. I wasn’t engaged with; I knew next to nothing of the Toronto literary community or any other literary communities. I did have plenty of my own ideas based on having gone to University in the distant past, and also from all the thoughts and theories that sprang into my head from what I was doing at the time, which was studying contemporary psychological needs-theory astrology.

I did want to explore my coming-of-age years, to excavate them and find an underlying structure. So Flip Turn is a “true story” but not in any conventional narrative “true story” way. What I wanted to happen was for a different kind, an upside down or girl development narrative, arc to emerge.

Then, after writing Flip Turn I was reading ethicist, psychologist and feminist Carol Gilligan’s book In a Different Voice which describes the stages of young girls’ psychological and moral development as different from young boys, and it seemed to me, based on what Gilligan was describing, that what I had unearthed was the same thing.

That excited me, and yet it doesn’t appear any of Flip Turn’s readers are noticing any sort of unique arc in Flip Turn, mostly, so far readers just see it as lacking arc, which I suppose could be expected for two possibly connected reasons; if it’s a pattern that’s not all that recognizable in the first place why should it be recognized now? And/or perhaps I just haven’t conveyed the thing all that well.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Yes, what writers do should be important in the larger culture. Here in Toronto we have a big writers’ scene, but it seems pretty insular; I see the same people at the different readings. Which isn’t meant as a criticism of the scene, maybe I’m asking the wrong things of it, I just wonder why it’s not more, why there aren’t more regular non-writer people attracted to it.

Flip Turn, which is set in London Ontario, my home town, received a beautiful write up in the London Free Press, by columnist James Reaney (yes, the son of). His column is called “My London.” Naturally the column’s focus was on the book’s relationship to the city, and on me and my history as Londoner.

I liked that. I like the thought of the book being about the world we live in, and in that way inviting, almost, personal participation by the reader, or a feeling of us-ness, and the writing delivering a kind of meaning to who and where we exist.

Anyway that’s how I experienced Canadian Literature as a young adult. Reading it woke me up to the idea of my being in the world and as counting as a participant in the world in this special way I wasn’t aware of previously.

Angie Abdou recently reviewed Flip Turn. Angie is a novelist, reviewer and academic. One of her focuses is sports culture. It was gratifying to be recognized in her review as interrogating “the culture of competitive swimming with great vigour and ruthlessness.” So yes, cultural critic is good too.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Last summer, prior to learning of Flip Turn’s publication acceptance at Mansfield, I asked poet and editor Joan Guenther to edit the aforementioned Pinery project. At that time, we (my husband and I) were thinking of self publishing and I felt extremely uncomfortable with the thought of putting it out there without a second set of trusted editorial eyes giving it the okay.

I think editors are extraordinary beasts, and can even be considered collaborators. I’m having a poem included in this spring’s Toronto Poetry Vendors series, and I was excited by editor Carey Toane’s treatment of the piece I submitted, which was, in the first place (despite my protestations above of not recognizing genre distinctions) more a piece of prose then a poem. Carey’s editorial suggestions, which had mostly to do with taking out its more narrative components, taught me a lot. I liked what the piece turned into, but sheepishly wonder whether it would be more appropriate that Carey get a collaborator credit rather than an editorial one.

Working with Stuart Ross on Flip Turn, I felt myself witness to a profound otherworldly experience. It seemed like Stuart simply, picked the novel up in his hands, like it was a clean wrinkled bed sheet from off the clothes line, and shook it out in such a way as to get it to smooth out into its proper form.

I love editing my own work, it’s a part of my creative process, but really, isn’t it best to get someone else to shake the thing out?

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

The best advice I’ve received was from a grade eight art classmate. Regarding our assignment, to draw from the local architecture, which I had no clue how to do, she simply recommended, “Draw what you see.” I did. I followed how I saw the lines of the house springing out in directions another part of my mind was telling me made no sense, was wrong of me and illogical; yet it worked. I drew the house and the completed work even received the recognition of getting taped up on the art class wall. My classmate’s instructions on how to draw has translated well for me as good advice on how to write.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (short stories to novel to critical prose to journalism)? What do you see as the appeal?

The way I like to write is kind of prose, kind of poetry. In terms of the reader response to Flip Turn I find myself in odd position. The novel readers expect Flip Turn to do what a regular novel does and don’t quite understand its trajectory and don’t really take into account or even notice its poetic sensibility. Meanwhile, on the extreme end of those on the poetry side of the divide, some won’t even pick the book up because it has that bad five letter word “novel” on the cover. To get back to your question, my issue isn’t about moving between genres, it’s about being between them.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I work full time at my day job. I am working on changing this to give myself more writing time. When I wrote Flip Turn, I quit my job and was able to get in a regular daily writing routine. I got my son up in the morning, took him to school, went for a swim, then came home and wrote from about 10am to 3pm, at which point, I put my writing down and went to pick up my son from school. That was a great routine.

Before daylight savings I was managing to get myself up an hour before work, and get some writing in then. I know other writers who do it that way, get up early, but I can’t say I’ve had consistent success at that yet, though I’m not ready to give up. I’ve actually accumulated a fair amount of half decent writing on my transit commute to and from work.

I’m close to temporarily reconciling myself to work more on poetic projects that don’t demand the psychic/psychological (not sure what the word for the state is) connection necessary to the holding onto or driving down into a deeper narrative theme the way I did when writing Flip Turn.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I love writing from inside my life experience. I am inspired by planets and outer space and the astrology of it too. Up until now I’ve been pretty gushy and haven’t had a lot of difficulty sourcing inspiration. I can see that possibly changing upcoming as I begin to mature as a writer and look for greater challenges.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Pine needles, pee, wet.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

In the Pinery Trip, Larry’s drawings came first, my writing followed. So, echphrasis, kind of sort of, because while the drawings were the starting point, the writing was also based on the shared experience of a family camping trip, so sometimes the writing was quite digressive, writing to a space connected to the space evoked by the drawing. I do get quite inspired by music, but I’m too sensitive. I have seen myself just write to the music when I don’t want to be writing to the music, so I don’t usually listen to music when I write. Nature, definitely! Science! Yes, love reading, especially about the planets and outer space, and picking up from there.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I think I am still primarily influenced by my early literature studies. I have been exposed to a lot of contemporary Canadian poets through Margaret Christakos’ Influency Salon and I feel going forward, in terms of my writing, I am still just beginning to mulch or incorporate these newer influences.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I would like to get more highly educated. I would like to travel to interesting places and stay for a while and write in those places/spaces.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Novel published? Check!

List of getting published in other venues growing? Check!

Favourite other people to hang out with, writers? Check!

Still have a full time day job? …………drats... check.

I am still working hard at claiming writer status. I have not raised my sites to occupying another.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I always liked writing. I always had a talent for it. Your question makes me think writing wasn’t all that conscious of a decision for me; more of an “it happening to me” than a “my happening to it” kind of thing.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I seem to have lost the knack of feeling the “great book” reading experience. Reading Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle as a teenager shocked and thrilled me. It seemed I had stumbled upon a hilarious secret world and based on how everyone around me was acting or failing to act, it looked like I was going to be able to keep it. I felt the same way when I was introduced to David W McFadden’s Trips around Lake Huron and Erie during my university years.

Regarding film I do have a thing for Hitchcock. In particular I recently saw Shadow of a Doubt. I do so love Hitchcock’s attention to small town social order and how small slip by small, what is sweet and whole and right turns dark and pulls everyone into it helplessly.

20 - What are you currently working on?

As mentioned above, it seems, for the moment, because of the demands of my day job, I must focus on theme based projects without deeper narratives. I am working on something of that ilk right now, but it will need more time before I will know whether it’s working.

I’ve been attending a poetry writing workshop run by Hoa Nguyen from which I am learning new writing strategies. I had planned to attend another Margaret Christakos’ Influency Salon, a forum that helped me in developing a critical understanding of contemporary poetry and invited me to make contributions to it, but sadly, for all, the Salon has been cancelled.

Since Flip Turn is a book with an appeal to young adults I plan on doing more high school visits; I did one recently and it was so interesting to get students’ feedback. As well, I think there’s a “using personal astrological symbolism to develop your writing” course that’s been mulching at the back of my mind for some time. Perhaps it is time to let that project idea hatch.

Looking forward I am planning on finding a way to take a leave from my day job to give me the kind of time and space I need to delve into a project with a deeper extended narrative, like I was able to do previously with Flip Turn.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book Flip Turn just came out this past November. Being in the state of waiting and wanting to find a publisher and have Flip Turn published and to be recognized as a real bona fide writer is done with. Now that it has happened, I’m published, I’m a “for real” writer, I want more. I am less willing to put up with putting off writing. I’m meaner and crankier.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

At this point in time, I don’t relate very well to those different categories. I think how I write is a blend. I do like to write from my experience, but my experience is tenuous. It is uncertain. I am uncertain. I do like strong form though what I see as strong form others don’t necessarily.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

The method that worked well for me writing Flip Turn was quickly jotting down the structuring ideas that were coming to me, in point form. Then I would fill in, or write to those different overview or structuring points. The structure wasn’t necessarily linear but to my mind formed a larger connecting/disconnected narrative. There are also times I can just go on a long writing jag and the writing will circle back the way I need it to, or it needs to, but other times I am aware I have lost track of parts.

Often just getting anything down is fine. Sometimes what I start out with doesn’t change that much, other times it morphs into something completely different.

4 - Where does fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

With Flip Turn I intended for it to be an extended narrative or book. I had an idea of beginning, in betweenness and end. The intention was similar with The Pinery Trip, a (yet unpublished) project I collaborated on with my husband (artist Larry Eisenstein), made up of pairings of his drawings with my writing. While Pinery has narrative components it’s not an extended narrative, it reads more like a book of poetry. But, again, the plan was for it to be a theme based book. I do too write little solo vignettes not intended to be part of a larger project. Or maybe they’ve just never found their sister and brother parts to make them part of something bigger. I’m working on something now, small pieces, based on a theme. Overall, at this time, I do like having a larger framework to work within.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I don’t have a lot of experience giving readings yet. I’ve given some readings that I think went beautifully, that I enjoyed and felt the audience connected to. I’ve given others I have been disappointed in. I think the strength of my reading can have some influence over the audience reception. But there is also a degree of the intangible in the audience. Maybe I should try to think of that as something that could be fun.

I have a reading upcoming next week at which I hope to simply experience whatever the audience response is, to allow getting a feeling back or another take on what my writing is about, rather than pushing for a specific response.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I wrote Flip Turn in something of a vacuum. I wasn’t engaged with; I knew next to nothing of the Toronto literary community or any other literary communities. I did have plenty of my own ideas based on having gone to University in the distant past, and also from all the thoughts and theories that sprang into my head from what I was doing at the time, which was studying contemporary psychological needs-theory astrology.

I did want to explore my coming-of-age years, to excavate them and find an underlying structure. So Flip Turn is a “true story” but not in any conventional narrative “true story” way. What I wanted to happen was for a different kind, an upside down or girl development narrative, arc to emerge.

Then, after writing Flip Turn I was reading ethicist, psychologist and feminist Carol Gilligan’s book In a Different Voice which describes the stages of young girls’ psychological and moral development as different from young boys, and it seemed to me, based on what Gilligan was describing, that what I had unearthed was the same thing.

That excited me, and yet it doesn’t appear any of Flip Turn’s readers are noticing any sort of unique arc in Flip Turn, mostly, so far readers just see it as lacking arc, which I suppose could be expected for two possibly connected reasons; if it’s a pattern that’s not all that recognizable in the first place why should it be recognized now? And/or perhaps I just haven’t conveyed the thing all that well.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Yes, what writers do should be important in the larger culture. Here in Toronto we have a big writers’ scene, but it seems pretty insular; I see the same people at the different readings. Which isn’t meant as a criticism of the scene, maybe I’m asking the wrong things of it, I just wonder why it’s not more, why there aren’t more regular non-writer people attracted to it.

Flip Turn, which is set in London Ontario, my home town, received a beautiful write up in the London Free Press, by columnist James Reaney (yes, the son of). His column is called “My London.” Naturally the column’s focus was on the book’s relationship to the city, and on me and my history as Londoner.

I liked that. I like the thought of the book being about the world we live in, and in that way inviting, almost, personal participation by the reader, or a feeling of us-ness, and the writing delivering a kind of meaning to who and where we exist.

Anyway that’s how I experienced Canadian Literature as a young adult. Reading it woke me up to the idea of my being in the world and as counting as a participant in the world in this special way I wasn’t aware of previously.

Angie Abdou recently reviewed Flip Turn. Angie is a novelist, reviewer and academic. One of her focuses is sports culture. It was gratifying to be recognized in her review as interrogating “the culture of competitive swimming with great vigour and ruthlessness.” So yes, cultural critic is good too.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Last summer, prior to learning of Flip Turn’s publication acceptance at Mansfield, I asked poet and editor Joan Guenther to edit the aforementioned Pinery project. At that time, we (my husband and I) were thinking of self publishing and I felt extremely uncomfortable with the thought of putting it out there without a second set of trusted editorial eyes giving it the okay.

I think editors are extraordinary beasts, and can even be considered collaborators. I’m having a poem included in this spring’s Toronto Poetry Vendors series, and I was excited by editor Carey Toane’s treatment of the piece I submitted, which was, in the first place (despite my protestations above of not recognizing genre distinctions) more a piece of prose then a poem. Carey’s editorial suggestions, which had mostly to do with taking out its more narrative components, taught me a lot. I liked what the piece turned into, but sheepishly wonder whether it would be more appropriate that Carey get a collaborator credit rather than an editorial one.

Working with Stuart Ross on Flip Turn, I felt myself witness to a profound otherworldly experience. It seemed like Stuart simply, picked the novel up in his hands, like it was a clean wrinkled bed sheet from off the clothes line, and shook it out in such a way as to get it to smooth out into its proper form.

I love editing my own work, it’s a part of my creative process, but really, isn’t it best to get someone else to shake the thing out?

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

The best advice I’ve received was from a grade eight art classmate. Regarding our assignment, to draw from the local architecture, which I had no clue how to do, she simply recommended, “Draw what you see.” I did. I followed how I saw the lines of the house springing out in directions another part of my mind was telling me made no sense, was wrong of me and illogical; yet it worked. I drew the house and the completed work even received the recognition of getting taped up on the art class wall. My classmate’s instructions on how to draw has translated well for me as good advice on how to write.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (short stories to novel to critical prose to journalism)? What do you see as the appeal?

The way I like to write is kind of prose, kind of poetry. In terms of the reader response to Flip Turn I find myself in odd position. The novel readers expect Flip Turn to do what a regular novel does and don’t quite understand its trajectory and don’t really take into account or even notice its poetic sensibility. Meanwhile, on the extreme end of those on the poetry side of the divide, some won’t even pick the book up because it has that bad five letter word “novel” on the cover. To get back to your question, my issue isn’t about moving between genres, it’s about being between them.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I work full time at my day job. I am working on changing this to give myself more writing time. When I wrote Flip Turn, I quit my job and was able to get in a regular daily writing routine. I got my son up in the morning, took him to school, went for a swim, then came home and wrote from about 10am to 3pm, at which point, I put my writing down and went to pick up my son from school. That was a great routine.

Before daylight savings I was managing to get myself up an hour before work, and get some writing in then. I know other writers who do it that way, get up early, but I can’t say I’ve had consistent success at that yet, though I’m not ready to give up. I’ve actually accumulated a fair amount of half decent writing on my transit commute to and from work.

I’m close to temporarily reconciling myself to work more on poetic projects that don’t demand the psychic/psychological (not sure what the word for the state is) connection necessary to the holding onto or driving down into a deeper narrative theme the way I did when writing Flip Turn.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I love writing from inside my life experience. I am inspired by planets and outer space and the astrology of it too. Up until now I’ve been pretty gushy and haven’t had a lot of difficulty sourcing inspiration. I can see that possibly changing upcoming as I begin to mature as a writer and look for greater challenges.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Pine needles, pee, wet.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

In the Pinery Trip, Larry’s drawings came first, my writing followed. So, echphrasis, kind of sort of, because while the drawings were the starting point, the writing was also based on the shared experience of a family camping trip, so sometimes the writing was quite digressive, writing to a space connected to the space evoked by the drawing. I do get quite inspired by music, but I’m too sensitive. I have seen myself just write to the music when I don’t want to be writing to the music, so I don’t usually listen to music when I write. Nature, definitely! Science! Yes, love reading, especially about the planets and outer space, and picking up from there.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I think I am still primarily influenced by my early literature studies. I have been exposed to a lot of contemporary Canadian poets through Margaret Christakos’ Influency Salon and I feel going forward, in terms of my writing, I am still just beginning to mulch or incorporate these newer influences.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I would like to get more highly educated. I would like to travel to interesting places and stay for a while and write in those places/spaces.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Novel published? Check!

List of getting published in other venues growing? Check!

Favourite other people to hang out with, writers? Check!

Still have a full time day job? …………drats... check.

I am still working hard at claiming writer status. I have not raised my sites to occupying another.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I always liked writing. I always had a talent for it. Your question makes me think writing wasn’t all that conscious of a decision for me; more of an “it happening to me” than a “my happening to it” kind of thing.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I seem to have lost the knack of feeling the “great book” reading experience. Reading Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle as a teenager shocked and thrilled me. It seemed I had stumbled upon a hilarious secret world and based on how everyone around me was acting or failing to act, it looked like I was going to be able to keep it. I felt the same way when I was introduced to David W McFadden’s Trips around Lake Huron and Erie during my university years.

Regarding film I do have a thing for Hitchcock. In particular I recently saw Shadow of a Doubt. I do so love Hitchcock’s attention to small town social order and how small slip by small, what is sweet and whole and right turns dark and pulls everyone into it helplessly.

20 - What are you currently working on?

As mentioned above, it seems, for the moment, because of the demands of my day job, I must focus on theme based projects without deeper narratives. I am working on something of that ilk right now, but it will need more time before I will know whether it’s working.

I’ve been attending a poetry writing workshop run by Hoa Nguyen from which I am learning new writing strategies. I had planned to attend another Margaret Christakos’ Influency Salon, a forum that helped me in developing a critical understanding of contemporary poetry and invited me to make contributions to it, but sadly, for all, the Salon has been cancelled.

Since Flip Turn is a book with an appeal to young adults I plan on doing more high school visits; I did one recently and it was so interesting to get students’ feedback. As well, I think there’s a “using personal astrological symbolism to develop your writing” course that’s been mulching at the back of my mind for some time. Perhaps it is time to let that project idea hatch.

Looking forward I am planning on finding a way to take a leave from my day job to give me the kind of time and space I need to delve into a project with a deeper extended narrative, like I was able to do previously with Flip Turn.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

↧

↧

Profile of Peter Norman, with a few questions,

↧

Jessica Hiemstra, Self-Portrait Without a Bicycle

Rachel insisted Keira Jo be swaddled, not clothed.

She’s not a doll, she said. And besides

there are rituals reserved for mothers. The gentle

first tug of naked arms through cotton, white socks

on new feet. She didn’t want her daughter dressed

the first time by a mortician, lovingly or by rote. It was,

Rachel said, the most terrifying moment of my life—

preparing to hold her dead girl, a pixie,

she said, perfect. When I stooped over the box

Keira Jo was wearing a yellow toque, swaddled

in white, an almost-child. Small red face, perfect

lips. Plutarch, in Moralia, wrote not to be born is best

of all, and death better than life, but the wisdom

of Silenus is stilled by one small mouth at the breast,

a tiny heart—that sparrow, Rachel’s thumb

clutched by a small pink hand, any flutter

however small. (“A bowl of strawberries in an empty room”)

I don’t normally favour lyric poetry so overtly narrative, but there is something about the lyric of

Jessica Hiemstra’s second trade poetry collection, Self-Portrait Without a Bicycle (Emeryville ON: Biblioasis, 2012), that immediately takes hold. Given that she is also a working visual artist (her sketches adorn both cover and inside the collection), there is something of the rough sketch to some of these poems, deceptively rough but finely hewn, shockingly precise in quick, quiet lines. The collection is made up of a series of meditative poems that focus on smallness, from matters of the domestic to language to matters-of-fact, such as the poem “Well, the cat’s dead,” that opens with “I wasn’t fond of her but one dandelion in a jar / is pretty.”

Every so often, there might be a line that rankles, such as “I felt my skin grow taut.” in the otherwise strong poem “I told my first stranger I was pregnant,” but these near-cliché lines appear to be the exception, and not the rule. With references to the art of Alex Colville, Yann Martel, grandparents and children, these are poems grounded in the immediate world, open and completely bare, following the essential lines of quiet. Composed with such clarity and soft humour, what might a writer such as Jessica Hiemstra do, perhaps, with fiction? I would worry it might read too straight, as so much other contemporary fiction, but I would read a fiction that writes as these poems do, slipping in and around a directness more direct than confession.

Mom rescued Alex Colville from the library

and we took him home, tattered and torn. A librarian

had taken scissors to him, removed the nakedness,

left the guns. Mom gathered up the loose pages,

carefully taped the women back in. Violence, she said

against love. I didn’t know what she meant. Truth

lies in juxtaposition. Painting occurs, Alex says,

when I think of two disparate elements. That night

I opened Tragic Landscape on my lap and got lost

in the folds of cow beyond the soldier, still grazing,

as though death had taken nothing. I knew the man

was dead, but I searched the painting for a sign he was

sleeping. Later that year I was censored too, my Mrs. Milling,

who took my drawing of Adam and Eve and hid it

in her desk. She said I had made them too naked. Nakedness

makes us afraid. Imagine my mother hadn’t

stitched up the book, imagine just Pacific and Bodies

in a Grave, Belsen. I spent the evening thinking

about guns, women in bathtubs, artists at war. What makes

something indecent is not skin but scissors.

This morning I tried to buy The Art of Alex Colville,

but it was too expensive. Tomorrow I’ll try eBay,

perhaps someone doesn’t know what it’s worth.

↧

Mindmade Books: Cole, Werkman, Queneau and Frey,

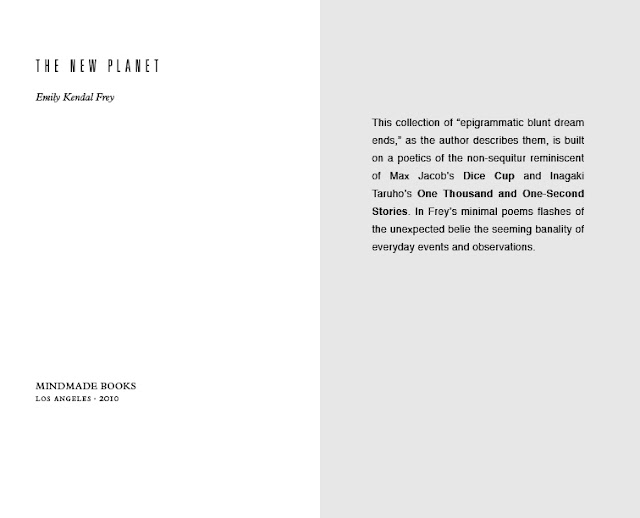

I received a small stack of publications from Los Angeles, California chapbook publisher Mindmade Books, including Norma Cole’s a little a & a (2002), H.N. Werkman’sTiksels (2007), Raymond Queneau’s FOR AN ARS POETICA (trans. Guy Bennett, 2009) and Emily Kendal Frey’s The New Planet (2010).

American poet Norma Cole, originally from Toronto [see my review of her selected poems here], is a bit of a moving target, rarely working the same forms twice. Her a little a & a is a polyphonic sequence of commentaries upon commentaries, a fragmented essay talking about poetry and art, storytelling, translation, myth and commodity. Composed as a fragmented piece, stretched out and sketched, it writes and translates an essay/conversation and an argument, collaged.

Become the object, love it and live it. When you look for a long time like that, do you see into or beyond? In those days we worked so hard to take the figure out.*

– But the scenario, would it identify and speak for it, something,

the present something relevant to the exhibition even at a tangent?

– You mean explain the show. Can’t it speak for itself?

– Not the point. Not explanation. Parallel play. Translation

– Libidinous.

– Rather than strictly superego, the translation as explanation ap-

proach ho hum.

– Carrousel.

– See what I mean?

*“It will have to be

something I’ll miss.”

de Kooning

The most fascinating work in the stack is Werkman’sTiksels, subtitled “1923-1929,” produced with an afterword by editor/publisher Guy Bennett. I admit to not knowing much of the history of concrete and visual poetry outside of Canada, but for some brief knowledge of Apollinaire’s work, Werkman appears to be one of the early modern producers of concrete and visual poetry, and much of this work is reminiscent of some of the works later produced in the 1960s by such as bpNichol, bill bissett and Steve McCaffery, among others. As Bennett writes to open his “Afterword”:

Hendrik Nikolaas Werkman (1882-1945) was a commercial printer by profession, but by all accounts not a very successful one. He was generally indifferent to money matters and apparently unskilled in running a business. When he suddenly needed to repay a substantial loan in the early 1920s his printing company foundered. In spite of the financial difficulties he faced, Werkman opted to look on this crisis as an opportunity for positive change: without abandoning commercial work he decided to pursue a lifelong interest in the visual arts, and he duly put the tools of his trade to artistic use. In 1923 he founded a magazine – The Next Call– that he would edit, write virtually single-handedly and print himself, and simultaneously embarked on a series of large-format abstract monographs that he called druksels (from the Dutch drukken– “to print”) which would eventually number more than 600. Both of these projects featured the innovative typographic design and printing techniques for which he has subsequently become known.

It was in 1923 that Werkman also began experimenting with the typewriter, creating a small body of predominantly abstract visual texts that he dubbed tiksels (from tikken, meaning “to type”). Whereas the pages of The Next Calland the druksel are alive with large colorful shapes and letter forms, the tikselsare graphically minimalist works whose basic visual unit is the tiny, monowidth typewriter character and whose color is that of the typewriter ribbon. Compositionally the tiksels are informed and limited by the machine used to produce them: horizontal and vertical lines and columns feature prominently, and rows of identical, repeated characters appear in nearly every piece. Far from creating monotony, these elements constitute a unifying formal grammar that gives coherence to the tiksels as an ensemble. Adding to their unique character is Werkman’s frequent use of analaphabetic which effectively removes them from the world of sound and situates them squarely in the visual realm. They were clearly intended to be seen and not heard, and this puzzles – how are we to read them, as poems or as pictures?

Raymond Queneau’sFOR AN ARS POETICA, translated from the French by Guy Bennett, is an eleven-part poetry sequence on the composition of poetry. An “ars poetica,” writing out writing out writing. He makes the composition of poetry sound like a kind of deliberate accident that somehow manages to incorporate everything.

1.

A poem’s indeed a trifling thing

little more than a cyclone in the Antilles

than a typhoon in the South China Sea

an earthquake in Anping

When there’s a flood on the Tang-Tse-Kiang

it’ll drown you 100,000 Chinese

bang

that’s not even a fitting subject for a poem

Indeed a trifling thing

We’re having some fun in our little village

we’re going to build a new school

we’re going to elect a new mayor and change the market days

we were at the center of the world now we’re near the river

ocean gnawing at the horizon

A poem’s indeed a trifling thing

Emily Kendal Frey is also the author of The Grief Performance (Cleveland State University Poetry Center, 2011) [see my reviewof such here], and her chapbook, The New Planet, is constructed almost entirely of tiny poems with enormous punches.

SMART

Am I smart enough to be androgynous?

Constantly shitting myself in your name.

Nothing is as beautiful as what is not beautiful.

Except sheet rock.

Frey’s poems feel a blend of Sarah Manguso-esque short fiction and the short poem, managing both without being tied to either. Constructed out of sentences, her prose poems strike at the very heart of whatever question she approaches. In some thirty pages, Frey is quickly becoming one of my favourite American emerging poets, for her sharp wit, and her use of the poetic sentence to not only make, but accumulate, sense; and from those accumulations, the smartest of poems.

GODS

I make a new planet out of rice.

No one wants to live on it.

No one even seems interested.

After a while, I sit down on my planet and eat what I’ve made.

Then I go across the road and hang out with the gods for a while.

↧

Letter to Norma Cole (some notes on the prose poem)

July 17, 2012

Ottawa, Canada

It’s been two years since I stayed in the nearly-former apartment of Toronto writers Stephen Cain and Sharon Harris, after helping them move into their new house. They had a box of books they were sending to Goodwill, and I picked out a couple of items, including the anthology you edited and translated, Crosscut Universe: Writing on Writing from France (Providence RI: Burning Deck, 2000), along with some other titles I probably shouldn’t mention. They had too many books. I’ve been meaning to thank you, and thank them as well.

The anthology contains works by sixteen writers, which the introduction describes as a series of “Texts, interviews, critical pieces, journal entries, letters, worknotes and at least one simple list make visible and audible an openwork of embodied voices in conversation, in the deliberate breaking open of intentionalities, isolating single elements at one extremity, multiple folds, complex rhythmic architectonics in the process of being constructed and deconstructed at the other.” You translated from the French works by Joë Bousquet, Emmanuel Hocquard, Claude Royet-Journoud, Anne-Marie Albiach, Raquel and others. It would be hard for anyone to not get caught up in the lyric prose line being presented. The lyric flows like water, here; why do so many lines of prose by English-language writers fail to float so smoothly in comparison?

The activity of writing is more than activity, as you wrote in your introduction, “Writing is action, the phenomenological self entering language, already a specific set of conditions within conditions.” I would enter the language, during daily writing sessions at The Good Neighbour Café on Annette Street, just by the Junction. The cadence and the lyric of the French abstract in some of the pieces immediately struck me, especially the work of Emmanuel Hocquard, which slowly began to impact the short short stories I’d been working on, and later, the prose poems I was only beginning to compose. Here is one of those stories:

I am writing a novel called ‘James Joyce in Montreal,’ to accompany the drawing you left. Ten chapters each featuring an entirely different character, but all sharing the same, ordinary name. There are no coincidences. In Labyrinths, Borges repeated, what we seek, is often nearby.

I admired Hocquard’s series of compact, straightforward lines that accumulated to become something slightly less concrete, and yet, far more than their sum. There was something to the connections made between and amid the disconnect that was astounding.

By that point, I’d been at least half a decade reading examples of the American prose poem, something far more prevalent than its Canadian counterpart, from writers such as Sheila E. Murphy, Lea Graham, Noah Eli Gordon, Joshua Marie Wilkinson, Kathleen Fraser and Rosmarie Waldrop. My own poems had been years experimenting with rhythm, sound and line breaks. I was in the midst of the “Miss Canada” manuscript, a book that stretched the length and breadth of 2010, composing poems that held and broke breath. I knew that once I had finished that collection, I wanted to move in another direction; I wanted to see what might happen if and when I stopped relying on line breaks and spacing. I wondered, what surprises might the prose poem hold? Once you learn how to do something, the painter Diane Woodward told me, move on.

Before this, I’d been intrigued by the use of the poetic line, and the sentence, through the work of Americans and Canadians alike, such as Cole Swensen, Lisa Robertson, Lisa Jarnot, Erin Mouré, David Donnell, Nicole Markotić and Robert Kroetsch. There is so much untapped potential in the sentence. How does one even start to approach the possibilities? I had long filed the prose poem away in the back of my head, waiting for other writing and editorial projects to come to maturity; to be able to bring my full attention to the form. I don’t need to completely understand a form to begin, but at least some kind of initial comprehension is required. Often, I know, the best way to understand is to simply begin. Specifically, I was struck by the way Hocquard’s prose-pieces blended elements of poetry, fiction and the short essay, opening up the form to a kind of “catch-all,” able to hold just about any idea, concept or subject matter.

ROBINSON METHOD

When Crusoe landed on his island after the shipwreck, he was not yet Robinson. He would be Robinson from the moment that, finding neither pen nor pencil in the jetsam, he liberated a cutter and some books. from these found objects would be born the method that names him.

Robinson speaks alone (V. Solitude), in words he learned while he was still Crusoe, words he arranges as memories, that is, as objects of memory-language. Robinson on his island acts like Crusoe before the shipwreck but makes the same thing resonate differently.

The island is elegiable. Cut off from the world, with the fated means that are his, Robinson will reproduce Crusoe’s world. He is a copier. And every copier, even the little classroom copier ripping off his desk partner, is an islander. Oliver Cadiot’s Future, ancient, fugitive is, just like Perec’s I remember, a splendid elegy. (Emmanuel Hocquard, trans. Norma Cole)

The French writing I’d predominantly been aware of previously had been Canadian, including the work of Nicole Brossard and AnneHébert, but remarkably little else in regards to poetry. Despite a series of translations through Coach House Press from the 1970s onward that focused on fiction, the divide between French and English Canada remains. Perhaps for this reason, it was the prose out of Quebec that resonated most, the novels of Dany Laferrièreand Daniel Paquin informing my writing far more than any Quebecois poets. It’s an interesting difference, to be influenced by the French writers of Canada versus the French writers from France. As you know, it’s an entirely different vocabulary. To understand the difference of influence might mean comprehending the mechanics of the language, and the divergence from European to Quebecois French. Something about the limits of translation or the delicacy of translating these differences. I have no idea; haven’t even begun.

Today I am not writing, I am seeing to the house of writing, and you are there, in the garden light. (Edith Dahan, from “Giudecca,” trans. Norma Cole)

In these works translated from French, there is such a lovely abstraction of subject and meaning the prose allows. It wraps around ideas as opposed to the physical. In contrast, I’ve been quite baffled reading Russell Edson, having heard he is considered the father of the American prose poem, and how much writers such as Deb Olin Unferth and Sarah Manguso (a writer I greatly admire) are influenced by his work. His poems read like short stories, known by Geist magazine and others as “postcard fiction.” Lydia Davis reads more lyric than these. Where is the poetry in Russell Edson? Whereas Unferth and Manguso have far surpassed him in quality and vigour, turning the influence of his prose poems into spectacular prose. I don’t understand the appeal. I suspect in some parts of the United States, this might be akin to a heretical statement.

This collection of yours has informed pieces of mine in various poetry manuscripts, an influence running through the length and breadth of my poetry since. Crosscut Universe: Writing on Writing from Francetaught me how to begin. Does that make sense? Perhaps it came at the right time. Perhaps I give the collection itself too much credit. I have been learning, learning and re-learning the sentence. There is a fragment of an interview I keep repeating, conducted by Kai Fierle-Hedrick in The Chicago Review (51:4/52:1, spring 2006), as Lisa Robertson responds: “I’m really a gentleman collector of sentences. I display them in cabinets.”

The Sentence

The sentence always translated from an other language, the sentence unfounded, the sentence of liquid shadows beyond which we do not look, writing it, (Dominique Fourcade, trans. Norma Cole)

In your collection, the distinctions between genres don’t seem to even exist. My explorations in short prose and the prose poem overlap so heavily, and yet, a line divides the two. Some have suggested my short stories might do better if I called them poems, but they aren’t poems; they’re stories. Despite their brevity, they each tell a deliberate narrative in a linear fashion. In the poems, I’m interested more in what I’ve long been exploring through the form – movement, sound and abstract, lyric exploration, composed more as an accumulation or collage. The logics needn’t be apparent and the narrative is non-existent. It might not be how I distinguish the forms generally, but its how I do for my own writing. There is no story, but instead, a series of sweeping gestures, such as this piece from the sequence “Escarpment pages,” a prose poem sequence from “If suppose we are a fragment.” The twelve poem sequence opens with a quote from Kathleen Fraser, “Dear other, I address you in sentences.”

The invention of writing

Ingrained, this resistance to struggle. Mathematical points. I repeat the arousal song of her borders, even as I step back. Sometimes I get turned around. Snow squalls, threatening daybreak. Had you ever wondered. Had she. We were marking up hours. Filament of the speed that the brain changes colour. We have not arrived. We are here. An experience of spiders. Saw you last from those uppermost branches. Or was that her. Words trickle down into feeling. New paper we press with first language, our hands.

I sound obsessed with boundaries, and perhaps I am, but as a series of guidelines as opposed to strict rules. I want to know where to blend one into the other. The works in Crosscut Universe, on the other hand, define no line at all. Have you read any of the work of Vancouver writer Michael Turner? His work manages the chimera between what isn’t entirely a poem, and isn’t entirely a story, but something else, entirely. I am seeking to open a series of possibilities. Or perhaps, I wasn’t listening in the right way until now. I’ve been interested, too, in discovering more of your own writing, the influences that some of these texts may have had, along the lines of influence I’ve seen from the Galacian in Erin Mouré’s poetry, or the French in the poetry of Cole Swensen and Rosmarie Waldrop. Perhaps I should start translating. Is it essential to know a second language to begin?

best,

↧

↧

HEADLIGHT anthology, #15-16

when all night longit pulls them down

Coming home from putting out a fire, how can they be expected to kiss the cheeks of their sleeping children and take out the leaking garbage and shuffle through the bills lying on the table and not drink the whiskey under the sink and spoon their wives while listening to their stories as well as their complaints and ask them questions and care about their answers and answer their questions and then sleep peacefully beside them without letting go when all night long it pulls them down, this threat and thrill of flame? (Hannah Rahimi, “Fragments,” HEADLIGHT #16)