↧

A short interview with Sachiko Murakami, Jacket2

↧

Jordan Abel, Un/inhabited

uninhabited

Changing horses frequently, one day out I had left Red River in my rear, but before me lay an country, unless I veered from my course and went through the Chickasaw Nation. Out toward Bear Canyon, where the land to the north rose brokenly to the mountains, Luck found the bleak stretches of which he had dreamed that night on the observation platform of a train speeding through the night in North Dakota,—a great white wilderness unsheltered by friendly forests, save by wild things that moved stealthily across the windswept ridges. This done, they would lead the ship to an part of the shore, beach her, and scatter over the mainland, each with his share of the booty. How lonely I felt, in that vast bush! Except for a very few places on the Ouleout, and the Iroquois towns, the region was . This was no country for people to livein, and so far as she could see it was indeed . But for the lazy columns of blue smoke curling up from the pinyons the place would have seemed . It appeared to be a dry, forest. In the vivid sunlight and perfect silence, it had a new, look, s if the carpenters and painters had just left it. it was in vain that those on board made remonstrances and entreaties, and represented the horrors of abandoning men upon a sterile and island; the sturdy captain was inflexible. The herbage is parched and withered; the brooks and streams are dried up; the buffalo, the elk and the deer have wandered to distant parts, keeping within the verge of expiring verdure, and leaving behind them a vast solitude, seemed by ravines, the beds of former torrents, but now serving only to tantalize and increase the thirst of the traveller. It kept on its course through a vast wilderness of silent and apparently mountains, without a savage wigwam upon its banks, or bark upon its waters. They were at a loss what route to take, and how far they were from the ultimate place of their destination, nor could they meet in these wilds with any human being to give them information. They forded Butte Creek, and, crossing the well-travelled trail which follows down to Drybone, turned their faces toward the country that began immediately, as the ocean begins off a sandy shore.

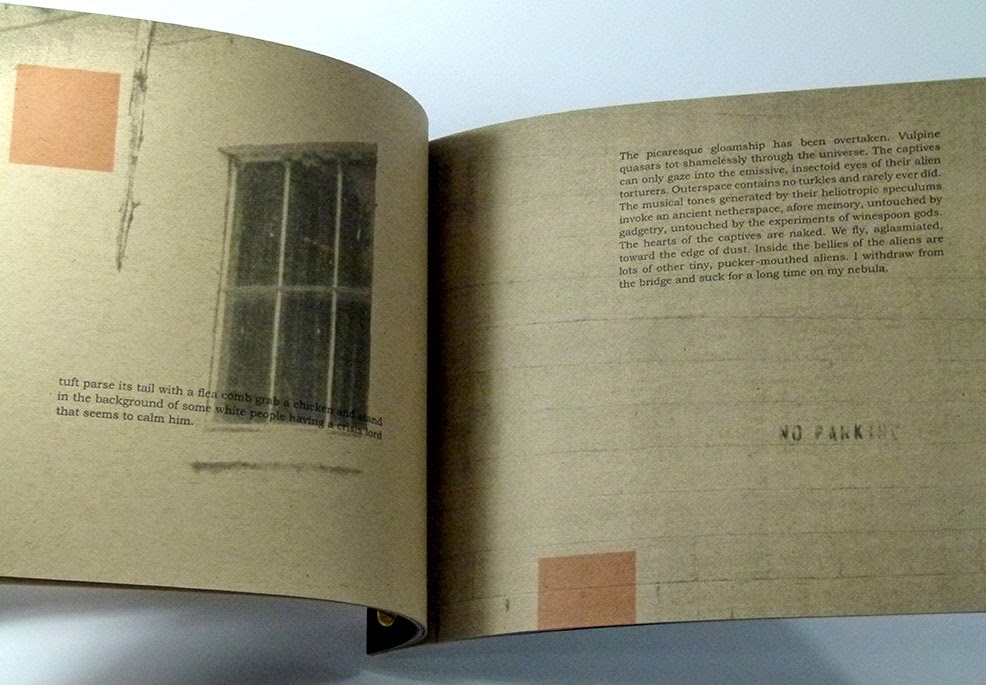

Jordan Abel’s Un/inhabited (Vancouver BC: Talonbooks/Project Space Press, 2014) continues the reclamation project begun through his first book, The Place of Scraps (Talonbooks, 2013). Whereas The Place of Scraps was constructed as a collection of fragments, erasures, scraps, texts, visuals and concrete poems constructed out of Canadian ethnographer and folklorist Marius Barbeau’s (1883-1969) canonical text, Totem Poles, Un/inhabited is constructed out of the texts of mass market works of “frontier” fiction. As Kathleen Ritter writes in her essay “Ctrl-F: Reterritorializing the Canon,” included at the back of the book: “A browse through the collection shows that most of these novels were written around the turn of the last century and, with titles like The Lonesome Trail and Other Stories, Gunman’s Reckoning, The Last of the Plainsmen, Way of the Lawlessand The Untamed, they are stereotypical of the romanticism of the frontier, the height of North American colonialism and a time when the indigenous population was being dispossessed of their lands and driven down to their lowest numbers in history as a direct result of European conflict, warfare and settlement.” The back cover describes the project:

Abel constructed the book’s source text by compiling ninety-one complete western novels found on the website Project Gutenberg, an online archive of public domain works. Using his word processor’s Ctrl-F function, he searched the document in its totality for words that relate to the political and social aspects of land, territory and ownership. Each search query represents a study in context (How was this word deployed? What surrounded it? What is left over once that word is removed?) that accumulates toward a representation of the public domain as a discoverable and inhabitable body of land.

There is something quite remarkable in the way that Abel, a Nisga’a writer from Vancouver, utilizes work that now exists in the public domain to reclaim and critique a representative and cultural space, using “conceptual writing [that] engages with the representation of Indigenous peoples in Anthropology through the technique of erasure.” Un/inhabited opens with erasure of specific words (uninhabited, settler, extracted, territory, indianized, pioneer, treaty, frontier, inhabited) before shifting to an erasure that shows the text almost as a cartographic map, before stripping the erasure down entirely, comparable to a depleting printer ink or photocopy toner cartridge. The only way these texts hold together is in the ways in which Abel allows them to degrade, before collapsing completely in on themselves. In an interview forthcoming at Touch the Donkey, he talks a bit about the compositional process of Un/inhabited:

After I finished writing Un/inhabited, there was a lot of material that essentially fell to the cutting room floor. I had been writing excessively, and knew that there would have to be substantial cuts for the project to be thematically coherent. As a result, there were many threads that had to be removed entirely. Some of those threads (minority, oil, afeared, etc.) were closely related to main conceptual project, but, for one reason or another, didn’t fit perfectly. Those threads were probably the most difficult to cut. Other threads (maps, speakers, urgency, etc.) were interesting explorations and worked individually, but were easy to separate from the main project. However, as the project continued, there were several threads that emerged that had coherent and discrete themes that weren’t dependent on the pieces in Un/inhabited. One of those threads explored the deployment of literary terms, and, surprisingly, seemed to be supported by the source text. That thread included many pieces: allegory, allusion, connotation, denouement, dialogue, flash back, hyperbole, identity, metaphor, motif, narrative, personification, simile, symbol, and theme.

To be honest, after I cut those pieces, I wasn’t really sure what to do with them. The pieces in Un/inhabited (settler, territory, frontier, etc.) worked partially because they explored themes of indigeneity, land use and ownership. Those pieces were actively working towards the destabilization of the colonial architecture of the western genre. But what were these other pieces doing? What did an exploration of the context surrounding the deployment of the word “allusion” accomplish?

I think, if I were to guess at an answer to my own question, that the thread of literary terms engages with an aspect of the western genre that is, at the very least, unusual. You don’t often think about the western genre being rich with metaphors or allusions or symbols, and, perhaps, it isn’t. But those words are there. Those words are doing something that we don’t normally associate with the traditional foundations of literary studies. There is an exploration here that, I think, subverts the tendencies of literary analysis by compressing and recontextualizing common analytic diction.

Right now, these pieces are not part of a separate project. But they easily could be. I think there’s more there to dig through. Other approaches that could be taken.

↧

↧

Boca Raton: trilogy,

Our third annual Boca Raton visit, at father-in-law’s condo. We spent a week in sunny Florida, arriving in April instead of our usual February [see last year’s reports parts one and two, and the year prior here, as well as a link to the recent chapbook that appeared with poems composed during that first visit], given some of Christine’s recent work-stuffs. Easter in Florida was interesting, although it flummoxed some of the plans that mother-in-law and dear sister might have had for us (Easter lunch/dinner), heading here on the immediate heels of Washington D.C. [see that report here]. Given that Washington was a work-trip, we of course had to return home before flying out again the following day. By the time we arrived on the Florida ground, I was so done with airplanes.

Upon arriving, we spent a few days with father-in-law and his wife, Teri, doing things such as going to lunch on the beach, going to the beach, and simply lounging about. We even found a park with a carousel [a park that, once Rose is a bit bigger, I imagine we’ll be spending plenty more time at]. Rose enjoyed the carousel and the running, the running, the running. She marvelled at the other children, as she does (somewhat confused and intrigued by them). And the running.

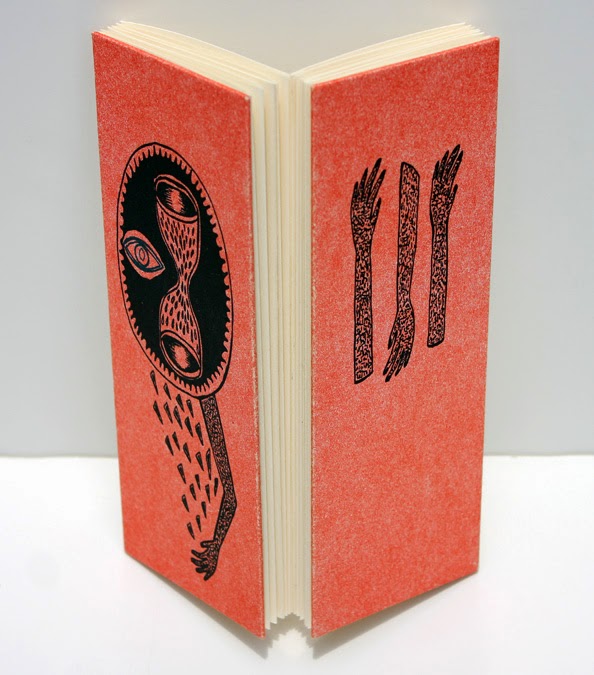

I poked at some poems, read some of the books [top photo: Susan Howe's Frame Structures: Early Poems 1974-1979] picked up on our Washington trip (among others), and generally tried not to move around too much. Worn out after an extended period of intense work (see my thirty Jacket2 commentaries, for example) and rather intense few days in Washington (again, see here). Once home, I plan to hit the ground running on poems and fiction and possibly some other schemes, both new and old, but for now, I am deliberately moving at a rather slow speed.

I move through Susan Howe, and Damian Rogers' second poetry collection. I had the wee lass colour upon a variety of postcards with crayon, to send to folk back home. Including a couple to big sister Kate.

We spent time on the beach. Rose, with her beach toys. Me, with my book(s).

Over the past week-plus, Rose was completely thrown off her nap and sleep schedule. Had a meltdown through the Ottawa airport coming here (which really never happens). Full-blown meltdown. At least they shoved us through security super-fast (an unexpected benefit, I suppose). Washington was what it was, so attempting to get her at least closer to her proper schedule while we’re down here. Hoping. Nearing the end of the week, we were starting to return to almost-normal. A couple of wee meltdowns. Hoping we can calm her within a day or so of home.

And then, of course, on Tuesday, we drove down into the bowels of Disneything.

I could have lived without Disneything, and had to be convinced. We spent the entire day there on Wednesday, with the morning at the Magic Kingdom and the afternoon into the evening at Epcot, and I enjoyed it far more than expected. Rose, of course, loved it; she eventually managed to sleep in her stroller, but didn't really let us sit down at all. At all. After ten hours of walking and wandering, rides, feeling overloaded by park and/or attempts to wander through gift shops, we were bone-tired. Sore upon sore.

Rose, who slept during the period between Magic Kingdom and Epcot.

The "Small World" ride was rather iconic, admittedly (I'm one of those who believes it was all 'better before Walt died,' and have good associations with some of the older films, productions, etcetera). I may be aware of some of the newer characters, but could really care less.

The gift shop overwhelmed. Every time I entered one, I felt as though I was beginning to shut down. Too much, too much, too much.

The gift shop overwhelmed. Every time I entered one, I felt as though I was beginning to shut down. Too much, too much, too much.

Don Quixote in the "Small World" ride, tilting. Ever tilting.

I saw Quixote references in Washington the week prior, also. Is this a push that I should be working to re-enter that novel-in-progress? Finally?

I admired the efficiencies of the Disney landscape. The workmanship and the cleanliness. They must employ a million billion people.

I felt overwhelmed by the range and the scope of their reach. Too much, too much. An American version of the city-state, much like the Vatican. Too much.

We wandered the park and rode the monorail (singing, "monorail. monorail. monorail..."). We ignored the characters, given that Rose doesn't know who any of them are anyway. She was happy to run, and sit on the occasional ride. She enjoyed eating.

She enjoyed looking at the fish in the "Finding Nemo" ride.

She enjoyed running. Running. Running.

And in the German Pavillion, where Christine had booked us dinner: misreading the menu and discovering we'd ordered MASSIVE MAGICAL BEERS. The food was incredible, as was the space and the music. I could have ignored the rest, and simply spent the day there.

Back, to hotel: where we almost immediately crashed. Removed footwear as in a cartoon, peeling back layers like a banana, hot steam rising from our sore, red toes and feet. Wooo-ooooo-ooooo-ooooshhhh.

Three-plus hour drive each way from the condo. Two nights. Rose and Christine some time in the kid-pool before we got into the car. Aiming the drive each way to her afternoon nap (which mostly worked).

Thursday night, upon home, hosting Mark Scroggins and his lovely family for dinner. Given we'd been hosted by them the past two years, we only figured it fair we'd offer our turn. And apparently not everyone else is at AWP (as facebook has suggested). Looking forward to this new critical book he's got forthcoming soon, which I recall him discussing last year.

Our final two days: as little as possible. Sleeping, occasional walks, quietly existing in the condo, aiming to get the wee babe back to some kind of schedule. Slow,

slow, so very slow.

And to Ottawa: to hit the ground running, perhaps. See about re-entering some of those fiction projects...

slow, so very slow.

And to Ottawa: to hit the ground running, perhaps. See about re-entering some of those fiction projects...

↧

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Amber McMillan

Amber McMillan is a teacher and writer living on Protection Island BC with her partner, daughter and two cats. Her first collection of poems We Can't Ever Do This Againis out this spring with Wolsak and Wynn.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Having made a book at all means that what I wrote will make it into the hands of someone other than me, and that makes me feel grateful. My most recent stab at things is a collection of short fiction that I haven't finished. I don't know how it's different yet because it has a lot of the same feelings as a book of poems. I know it is different, but I can't figure how just yet.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I'm still thinking about the distinctions between those genres and what they might mean, but put simply, poetry generally comes in smaller, more manageable sizes, and for that reason, was a good starting point for me. By contrast, a novel is a pretty daunting undertaking to my mind. I don't know how people write them, actually. It's very impressive to me that they do.

On a more personal level, the thought has crossed my mind that I prefer to write poetry because I don't have the creative or intellectual stamina to commit to anything longer, and that this might point to a character flaw in me that is worth considering.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

The "project" and the writing can come quickly. The slow parts are the periods where doubt comes in and I'm forced to turn over, defend, and sometimes toss out things that can't be pushed through to the other side for any number of reasons. But that's not really about writing; that process happens in all kinds of different areas in a person's life.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

The beginning is usually a line or a few particular words that I then try to bed into some coherent context. I haven't yet been able to begin a poem with the first word or first line and then write it to the end. I don't think I even want to do that. And I usually write a bigger poem then what I end up with. I write a bunch and then cut out a bunch and then it's done. I can't speak much more on the subject because I've only written one book and I'm not 100% sure how that actually happened.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I realized early that I would never make a good criminal because I'm a person that gets very nervous and clumsy when I feel there are too many eyes on me for any reason, like a public reading or a noon-hour bank robbery, for example.

I hope reading in public gets easier for me, and with that, comes with more pleasure than it does now, but I'm not convinced it ever will. On the other hand, I've noticed that there are folks that seem really comfortable reading in public and what they give is so confident and full that I can't help enjoying the experience of watching. These are people with a lot of practice and some natural talent for humour and sincerity, and that is something to see.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Maybe the current questions are something like: What's important to say? What's worth putting out there? Why? Then what?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

It's just one way to talk about things. One way among lots and lots of ways.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I think it's essential because everyone needs an editor, but I also think it can be difficult. But so what. Difficult is good too.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

For all its simplicity, "People will always do what they want to do" has turned out to be a very complicated truth, and has given me understanding into many of my life's frustrations. That one's from my mum.

Also, "Just be a nice person." - The Flaming Lips

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I don't have a routine. A typical day is about getting my kid ready for school, going to and from work, grocery shopping, sweeping, feeding the cats, paying bills, and sourcing out ways to get time to myself.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Alcohol, insomnia, vulnerability, quiet and boredom.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Wood stain and varnish. My Opa was a carpenter and had a furniture store in London, ON where he built chairs, tables, etc. He also used the store to show off the unfinished Mennonite furniture he would drive for hours to pick up in his truck. My cousins and I spent a lot of our weekend and after school hours in the furniture store because it was a family-run business and all of our parents worked there. Needless to say, Opa's workshop at the back of the store, the store itself, and the inside of his truck, all smelled like wood shavings, wood stain, and varnish. Even years later, when I no longer went to that store anymore, those smells were always around: on my family's clothes, in the garage, in Opa's second or third workshop that he kept in my mum's backyard. Just all my life.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

My ordinary influence is to address my own troubles by writing them out and trying to solve some menacing, nagging question. So, in that way, nature or music or science can be rigged up to serve any manner of metaphor to achieve that solution. Or to appear to solve. Or to come close to solving.

David W. McFadden also said, "Neither apologize nor forgive," which helps too.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I'm probably in the minority here, but reading criticism at university was the single most important reading I've done. I'm talking about scholarly essays by hardcore academics and theorists. Then later as an instructor, re-reading and discussing that criticism with my students doubled its importance. That kind of reading taught me how to organize my thinking in ways I have leaned on ever since.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I just really want to get over my fear of dogs. It's so inconvenient and makes me feel like such a weirdo.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Since I was a teenager, I wanted to be a doctor. I didn't have the grades though and so my parents encouraged me to go to art school.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I tried a couple of other things first like being in bands and studying drawing in college. These decisions brought good things and I don't regret them, but there's something unobtrusive and civil about writing poems that I couldn't achieve in my earlier attempts at art.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

So, I live with a man who had written a book before I met him. This book contained a life story close to his own. When it was published, I didn't read it and then I didn't read it for a year after it was published. The next year I read it and it was the last great book I read; Nathaniel G. Moore's Savage 1986-2011, which has since won the ReLit Award in the category of fiction, so I guess I'm not the only one who thought it was great.

19 - What are you currently working on?

A collection of stories about living on Protection Island, BC where I've just spent a year. This looks like non-fiction/fiction/poetry and it's hard to do. I've had to face and tread through a lot of questions about the ethics, integrity, goals for, and hidden motivations of having chosen to write this.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Having made a book at all means that what I wrote will make it into the hands of someone other than me, and that makes me feel grateful. My most recent stab at things is a collection of short fiction that I haven't finished. I don't know how it's different yet because it has a lot of the same feelings as a book of poems. I know it is different, but I can't figure how just yet.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I'm still thinking about the distinctions between those genres and what they might mean, but put simply, poetry generally comes in smaller, more manageable sizes, and for that reason, was a good starting point for me. By contrast, a novel is a pretty daunting undertaking to my mind. I don't know how people write them, actually. It's very impressive to me that they do.

On a more personal level, the thought has crossed my mind that I prefer to write poetry because I don't have the creative or intellectual stamina to commit to anything longer, and that this might point to a character flaw in me that is worth considering.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

The "project" and the writing can come quickly. The slow parts are the periods where doubt comes in and I'm forced to turn over, defend, and sometimes toss out things that can't be pushed through to the other side for any number of reasons. But that's not really about writing; that process happens in all kinds of different areas in a person's life.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

The beginning is usually a line or a few particular words that I then try to bed into some coherent context. I haven't yet been able to begin a poem with the first word or first line and then write it to the end. I don't think I even want to do that. And I usually write a bigger poem then what I end up with. I write a bunch and then cut out a bunch and then it's done. I can't speak much more on the subject because I've only written one book and I'm not 100% sure how that actually happened.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I realized early that I would never make a good criminal because I'm a person that gets very nervous and clumsy when I feel there are too many eyes on me for any reason, like a public reading or a noon-hour bank robbery, for example.

I hope reading in public gets easier for me, and with that, comes with more pleasure than it does now, but I'm not convinced it ever will. On the other hand, I've noticed that there are folks that seem really comfortable reading in public and what they give is so confident and full that I can't help enjoying the experience of watching. These are people with a lot of practice and some natural talent for humour and sincerity, and that is something to see.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Maybe the current questions are something like: What's important to say? What's worth putting out there? Why? Then what?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

It's just one way to talk about things. One way among lots and lots of ways.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I think it's essential because everyone needs an editor, but I also think it can be difficult. But so what. Difficult is good too.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

For all its simplicity, "People will always do what they want to do" has turned out to be a very complicated truth, and has given me understanding into many of my life's frustrations. That one's from my mum.

Also, "Just be a nice person." - The Flaming Lips

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I don't have a routine. A typical day is about getting my kid ready for school, going to and from work, grocery shopping, sweeping, feeding the cats, paying bills, and sourcing out ways to get time to myself.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Alcohol, insomnia, vulnerability, quiet and boredom.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Wood stain and varnish. My Opa was a carpenter and had a furniture store in London, ON where he built chairs, tables, etc. He also used the store to show off the unfinished Mennonite furniture he would drive for hours to pick up in his truck. My cousins and I spent a lot of our weekend and after school hours in the furniture store because it was a family-run business and all of our parents worked there. Needless to say, Opa's workshop at the back of the store, the store itself, and the inside of his truck, all smelled like wood shavings, wood stain, and varnish. Even years later, when I no longer went to that store anymore, those smells were always around: on my family's clothes, in the garage, in Opa's second or third workshop that he kept in my mum's backyard. Just all my life.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

My ordinary influence is to address my own troubles by writing them out and trying to solve some menacing, nagging question. So, in that way, nature or music or science can be rigged up to serve any manner of metaphor to achieve that solution. Or to appear to solve. Or to come close to solving.

David W. McFadden also said, "Neither apologize nor forgive," which helps too.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I'm probably in the minority here, but reading criticism at university was the single most important reading I've done. I'm talking about scholarly essays by hardcore academics and theorists. Then later as an instructor, re-reading and discussing that criticism with my students doubled its importance. That kind of reading taught me how to organize my thinking in ways I have leaned on ever since.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I just really want to get over my fear of dogs. It's so inconvenient and makes me feel like such a weirdo.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Since I was a teenager, I wanted to be a doctor. I didn't have the grades though and so my parents encouraged me to go to art school.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I tried a couple of other things first like being in bands and studying drawing in college. These decisions brought good things and I don't regret them, but there's something unobtrusive and civil about writing poems that I couldn't achieve in my earlier attempts at art.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

So, I live with a man who had written a book before I met him. This book contained a life story close to his own. When it was published, I didn't read it and then I didn't read it for a year after it was published. The next year I read it and it was the last great book I read; Nathaniel G. Moore's Savage 1986-2011, which has since won the ReLit Award in the category of fiction, so I guess I'm not the only one who thought it was great.

19 - What are you currently working on?

A collection of stories about living on Protection Island, BC where I've just spent a year. This looks like non-fiction/fiction/poetry and it's hard to do. I've had to face and tread through a lot of questions about the ethics, integrity, goals for, and hidden motivations of having chosen to write this.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

↧

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Shannon Webb-Campbell

Shannon Webb-Campbell [photo credit: Meghan Tansey Whitton] is an award-winning poet, writer, and journalist of mixed Aboriginal ancestry. She is the inaugural winner of Egale Canada’s Out in Print Award and was the Canadian Women in Literary Arts 2014 critic-in-residence. Still No Word (Breakwater Books) is her first collection of poems. She lives in Halifax.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Still No Word just came out yesterday, so it’s hard to say how it’s changed my life. It feels like encountering something extraordinary and peculiar, like swimming backwards inside of a whale.

These past few weeks leading up to the release, I was met with an unexpected storm of anxiety. I oscillated from wanting to throw up, to collecting rocks to fill my pockets for my farewell walk into the cold sea. I searched for escape routes, faraway places where I could reinvent, change name, become another. I wanted to crawl out of my skin, drink myself blind.

Apparently, this is all normal behavior of first timers, typical of vulnerability even. The book has been unleashed into the world, and I am still here. Now I’m more worried about the whale.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I began as a poet. I’ll die as a poet.

Though, I’ve previously published several creative non-fiction pieces, letters, poems and fictions in anthologies, including: Where The Nights Are Twice As Long: Love Letters of Canadian Poets (Goose Lane 2015), Out Proud: Stories of Courage, Pride, and Social Justice (Breakwater Books 2014), MESS: The Hospital Anthology (Tightrope Books 2014), She’s Shameless Women Write About Growing Up, Rocking Out and Fighting Back (Tightrope Books 2009) and GULCH: An Assemblage of Poetry and Prose (Tightrope Books 2009).

My next piece is a non-fiction story of rape and isolation set in Malta published in This Place A Stranger: Canadian Women Travelling Alone (Caitlin Press 2015).

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I start by circling myself. I stare out the window. I question my fate. I discourage myself before I even begin. And these are good days.

Often words and lines come when I’m not thinking about writing. This morning, shuffling around like an out of shape ballerina on Halifax’s iced-laced sidewalks, a stanza came. I can be at yoga, making lunch, or driving down the highway. Poetry has its own time clock; it never punches in or out.

Many lines come after crawling into bed, the time we’re most adrift, somewhere between worlds. Rarely do I cough up a poem. They all start unexpectedly. Most go through several drafts, weather systems, moods, and typically begin or end around the first libation of the day.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Poems happen. My job is to keep the channel open, to listen, witness, and document. I didn’t know the poems in Still No Word would ever become a book; they were orphans who needed a home.

I’m thankful Breakwater Books gave my poems a roof over their heads, and food in their bellies. These poems belong to Newfoundland. I suspect the next book will be written with a different intention, from another vantage point.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Astrologically, I embody Gemini, so duplicity is a constant state. I crave solitude and wildness. Poetry befits this calling. I enjoy the tucked-in nature of my work, spending hours, days, seasons playing with words, but I struggle with the solitary aspect. Many days, it goes against my nature.

Readings are a wonderful excuse for poets to gather, honour craft and community. We need to hear one another’s voices in order to find our own. We need an excuse to get outside ourselves, and witness one another’s tragedies and belly laughs. We need our tribe.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I live my life close to the bone, sucking on its marrow. Sometimes I’m on the brink, other times looking over. All I know, I’m a seeker. Poetry is both call and answer. It saves my life over and over.

Many of my questions reel around identity, ancestry, belonging, that constant nagging notion of home, rivers of grief, fragments of abuse, sexuality, and longing. I think we’re all poems.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Writers offer cardinal direction, we are the compass of a culture. Some of us are mythmakers, mapmakers, others schemers. Call us documentarians, or even translators, but we’re all witnesses here in the universe’s grand symphony.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I love the editorial process. Susan Musgrave catcalled me, created a safe space both dangerous enough for poetry and an incubator for a closeted poet. My editor James Langer at Breakwater was rough, yet insightful. He wanted more of a fight, but we both got our way in the end.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

“There is a vitality, a life force, an energy, a quickening that is translated through you into action, and because there is only one of you in all of time, this expression is unique. And if you block it, it will never exist through any other medium and it will be lost. The world will not have it,” Martha Graham to Agnes De Mille.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

All forms inform another.

Last year, as Canadian Women In Literary Arts critic-in-residence 2014, I was given a platform to examine how poetry informs criticism, and how criticism informs poetry.

I wrote several book reviews, examining works from Amber Dawn’s How Poetry Saved My Life: A Hustler’s Memoir (Arsenal Pulp) to Sylvia D. Hamilton’s I Alone Escaped To Tell You (Gaspereau Press). I labored over critical essays, which led to attending the Scotiabank Giller Prize Gala in Toronto, and published An Incomplete Manifesto for CWILA. Criticism relies on analysis, close reading, and creative nerve. So does poetry.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I wish there were hours allotted, strict routines, and diligent follow through. But I’m more of a wildcard. Mostly, I write when I force myself to. Most days begin with coffee, a notebook, and eventually, I open my computer.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I let go, and stop forcing myself. In stepping away from the words, I return to the living. Eventually, I exhaust myself with life’s carousel, and wash ashore, find myself back on land, looking out to sea, ready to write.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Cigarette smoke on fresh laundry (the smell of my grandmother).

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Atlantic Canada is instrumental in my work, whether it’s the harsh, rugged coastlines, or the vast, merciless ocean. Everything is hardship and endurance, the essentials. It’s my ancestral lands. I often threaten to move away due to weather extremes, yet never stray long enough to lose my place.

Though, to keep with McFadden’s insight, several poems in my book have kinfolk poems, including “Last View of Bell Island,” a sister to a suite of poems by Sue Sinclair and her various views of Bell Island. “Wintering,” gives nod to Rainer Maria Rilke, and my poem “Doubles,” is a sibling poem to a stanza in Sue Goyette’s “Psychic,” from her stunning book, Undone (Brick Books).

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Sylvia Plath’s work, especially her poems and journals, though The Bell Jar has a forever place in my being. Winter after winter, I return to Mary Oliver, especially when the living doesn’t go so easy. Writers like Simone de Beauvoir, Leonard Cohen, Zoe Whittall, Brian Brett, Lisa Moore, all the Susan’s (Musgrave, Goyette, Sinclair), Elizabeth Bishop, Shalan Joudry, Joseph Boyden, Anne Carson, Ivan Coyote, Anna Camilleri, Amber Dawn and Jeanette Winterson all call out.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I’d like to go for a hot air balloon ride. Visit Greece. Learn another language, especially Mi’kmaq. Live in a foreign country. Write a novel. Swim with mermaids. Sing a duet. Sail around the world. Maybe visit the moon.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I’ve worn many hats. I’ve been a photographer, a bookseller, shopkeeper, camera sales person, barista, art teacher, and nanny. Some days, I think I’d like to be a synchronized swimmer, own a dress shop, become a chef, or a milliner. My deepest aspirations are to teach creative writing at a college or university, so perhaps, in my own way, I can become all these things.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

The writing made me write. I blame the words.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I’ve just finished reading Lidia Yuknavitch’s The Chronology of Water: A Memoir (Hawthorne Books & Literary Arts), where she writes, “ In water, like in books – you can leave your life.” Words to live by.

Sarah Mian’s debut novel, When The Saints (Harper Collins), could be my favourite book out of Atlantic Canada this year.

As for the last great film, I’m still basking in the glow of Bruno Barreto’s Reaching For The Moon, the love story of Elizabeth Bishop and Brazilian architect Lota de Macedo Soares. I can’t even admit here how many times I’ve re-watched it.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Currently, I am working on a collection of linked stories, and attempting to write my first play for Queer Acts Theatre Festival. The odd poem, letter or fragment seems to intervene.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Still No Word just came out yesterday, so it’s hard to say how it’s changed my life. It feels like encountering something extraordinary and peculiar, like swimming backwards inside of a whale.

These past few weeks leading up to the release, I was met with an unexpected storm of anxiety. I oscillated from wanting to throw up, to collecting rocks to fill my pockets for my farewell walk into the cold sea. I searched for escape routes, faraway places where I could reinvent, change name, become another. I wanted to crawl out of my skin, drink myself blind.

Apparently, this is all normal behavior of first timers, typical of vulnerability even. The book has been unleashed into the world, and I am still here. Now I’m more worried about the whale.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I began as a poet. I’ll die as a poet.

Though, I’ve previously published several creative non-fiction pieces, letters, poems and fictions in anthologies, including: Where The Nights Are Twice As Long: Love Letters of Canadian Poets (Goose Lane 2015), Out Proud: Stories of Courage, Pride, and Social Justice (Breakwater Books 2014), MESS: The Hospital Anthology (Tightrope Books 2014), She’s Shameless Women Write About Growing Up, Rocking Out and Fighting Back (Tightrope Books 2009) and GULCH: An Assemblage of Poetry and Prose (Tightrope Books 2009).

My next piece is a non-fiction story of rape and isolation set in Malta published in This Place A Stranger: Canadian Women Travelling Alone (Caitlin Press 2015).

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I start by circling myself. I stare out the window. I question my fate. I discourage myself before I even begin. And these are good days.

Often words and lines come when I’m not thinking about writing. This morning, shuffling around like an out of shape ballerina on Halifax’s iced-laced sidewalks, a stanza came. I can be at yoga, making lunch, or driving down the highway. Poetry has its own time clock; it never punches in or out.

Many lines come after crawling into bed, the time we’re most adrift, somewhere between worlds. Rarely do I cough up a poem. They all start unexpectedly. Most go through several drafts, weather systems, moods, and typically begin or end around the first libation of the day.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Poems happen. My job is to keep the channel open, to listen, witness, and document. I didn’t know the poems in Still No Word would ever become a book; they were orphans who needed a home.

I’m thankful Breakwater Books gave my poems a roof over their heads, and food in their bellies. These poems belong to Newfoundland. I suspect the next book will be written with a different intention, from another vantage point.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Astrologically, I embody Gemini, so duplicity is a constant state. I crave solitude and wildness. Poetry befits this calling. I enjoy the tucked-in nature of my work, spending hours, days, seasons playing with words, but I struggle with the solitary aspect. Many days, it goes against my nature.

Readings are a wonderful excuse for poets to gather, honour craft and community. We need to hear one another’s voices in order to find our own. We need an excuse to get outside ourselves, and witness one another’s tragedies and belly laughs. We need our tribe.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I live my life close to the bone, sucking on its marrow. Sometimes I’m on the brink, other times looking over. All I know, I’m a seeker. Poetry is both call and answer. It saves my life over and over.

Many of my questions reel around identity, ancestry, belonging, that constant nagging notion of home, rivers of grief, fragments of abuse, sexuality, and longing. I think we’re all poems.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Writers offer cardinal direction, we are the compass of a culture. Some of us are mythmakers, mapmakers, others schemers. Call us documentarians, or even translators, but we’re all witnesses here in the universe’s grand symphony.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I love the editorial process. Susan Musgrave catcalled me, created a safe space both dangerous enough for poetry and an incubator for a closeted poet. My editor James Langer at Breakwater was rough, yet insightful. He wanted more of a fight, but we both got our way in the end.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

“There is a vitality, a life force, an energy, a quickening that is translated through you into action, and because there is only one of you in all of time, this expression is unique. And if you block it, it will never exist through any other medium and it will be lost. The world will not have it,” Martha Graham to Agnes De Mille.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

All forms inform another.

Last year, as Canadian Women In Literary Arts critic-in-residence 2014, I was given a platform to examine how poetry informs criticism, and how criticism informs poetry.

I wrote several book reviews, examining works from Amber Dawn’s How Poetry Saved My Life: A Hustler’s Memoir (Arsenal Pulp) to Sylvia D. Hamilton’s I Alone Escaped To Tell You (Gaspereau Press). I labored over critical essays, which led to attending the Scotiabank Giller Prize Gala in Toronto, and published An Incomplete Manifesto for CWILA. Criticism relies on analysis, close reading, and creative nerve. So does poetry.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I wish there were hours allotted, strict routines, and diligent follow through. But I’m more of a wildcard. Mostly, I write when I force myself to. Most days begin with coffee, a notebook, and eventually, I open my computer.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I let go, and stop forcing myself. In stepping away from the words, I return to the living. Eventually, I exhaust myself with life’s carousel, and wash ashore, find myself back on land, looking out to sea, ready to write.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Cigarette smoke on fresh laundry (the smell of my grandmother).

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Atlantic Canada is instrumental in my work, whether it’s the harsh, rugged coastlines, or the vast, merciless ocean. Everything is hardship and endurance, the essentials. It’s my ancestral lands. I often threaten to move away due to weather extremes, yet never stray long enough to lose my place.

Though, to keep with McFadden’s insight, several poems in my book have kinfolk poems, including “Last View of Bell Island,” a sister to a suite of poems by Sue Sinclair and her various views of Bell Island. “Wintering,” gives nod to Rainer Maria Rilke, and my poem “Doubles,” is a sibling poem to a stanza in Sue Goyette’s “Psychic,” from her stunning book, Undone (Brick Books).

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Sylvia Plath’s work, especially her poems and journals, though The Bell Jar has a forever place in my being. Winter after winter, I return to Mary Oliver, especially when the living doesn’t go so easy. Writers like Simone de Beauvoir, Leonard Cohen, Zoe Whittall, Brian Brett, Lisa Moore, all the Susan’s (Musgrave, Goyette, Sinclair), Elizabeth Bishop, Shalan Joudry, Joseph Boyden, Anne Carson, Ivan Coyote, Anna Camilleri, Amber Dawn and Jeanette Winterson all call out.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I’d like to go for a hot air balloon ride. Visit Greece. Learn another language, especially Mi’kmaq. Live in a foreign country. Write a novel. Swim with mermaids. Sing a duet. Sail around the world. Maybe visit the moon.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I’ve worn many hats. I’ve been a photographer, a bookseller, shopkeeper, camera sales person, barista, art teacher, and nanny. Some days, I think I’d like to be a synchronized swimmer, own a dress shop, become a chef, or a milliner. My deepest aspirations are to teach creative writing at a college or university, so perhaps, in my own way, I can become all these things.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

The writing made me write. I blame the words.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I’ve just finished reading Lidia Yuknavitch’s The Chronology of Water: A Memoir (Hawthorne Books & Literary Arts), where she writes, “ In water, like in books – you can leave your life.” Words to live by.

Sarah Mian’s debut novel, When The Saints (Harper Collins), could be my favourite book out of Atlantic Canada this year.

As for the last great film, I’m still basking in the glow of Bruno Barreto’s Reaching For The Moon, the love story of Elizabeth Bishop and Brazilian architect Lota de Macedo Soares. I can’t even admit here how many times I’ve re-watched it.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Currently, I am working on a collection of linked stories, and attempting to write my first play for Queer Acts Theatre Festival. The odd poem, letter or fragment seems to intervene.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

↧

↧

A short interview with Sachiko Murakami, Jacket2

↧

Jordan Abel, Un/inhabited

uninhabited

Changing horses frequently, one day out I had left Red River in my rear, but before me lay an country, unless I veered from my course and went through the Chickasaw Nation. Out toward Bear Canyon, where the land to the north rose brokenly to the mountains, Luck found the bleak stretches of which he had dreamed that night on the observation platform of a train speeding through the night in North Dakota,—a great white wilderness unsheltered by friendly forests, save by wild things that moved stealthily across the windswept ridges. This done, they would lead the ship to an part of the shore, beach her, and scatter over the mainland, each with his share of the booty. How lonely I felt, in that vast bush! Except for a very few places on the Ouleout, and the Iroquois towns, the region was . This was no country for people to livein, and so far as she could see it was indeed . But for the lazy columns of blue smoke curling up from the pinyons the place would have seemed . It appeared to be a dry, forest. In the vivid sunlight and perfect silence, it had a new, look, s if the carpenters and painters had just left it. it was in vain that those on board made remonstrances and entreaties, and represented the horrors of abandoning men upon a sterile and island; the sturdy captain was inflexible. The herbage is parched and withered; the brooks and streams are dried up; the buffalo, the elk and the deer have wandered to distant parts, keeping within the verge of expiring verdure, and leaving behind them a vast solitude, seemed by ravines, the beds of former torrents, but now serving only to tantalize and increase the thirst of the traveller. It kept on its course through a vast wilderness of silent and apparently mountains, without a savage wigwam upon its banks, or bark upon its waters. They were at a loss what route to take, and how far they were from the ultimate place of their destination, nor could they meet in these wilds with any human being to give them information. They forded Butte Creek, and, crossing the well-travelled trail which follows down to Drybone, turned their faces toward the country that began immediately, as the ocean begins off a sandy shore.

Jordan Abel’s Un/inhabited (Vancouver BC: Talonbooks/Project Space Press, 2014) continues the reclamation project begun through his first book, The Place of Scraps (Talonbooks, 2013). Whereas The Place of Scraps was constructed as a collection of fragments, erasures, scraps, texts, visuals and concrete poems constructed out of Canadian ethnographer and folklorist Marius Barbeau’s (1883-1969) canonical text, Totem Poles, Un/inhabited is constructed out of the texts of mass market works of “frontier” fiction. As Kathleen Ritter writes in her essay “Ctrl-F: Reterritorializing the Canon,” included at the back of the book: “A browse through the collection shows that most of these novels were written around the turn of the last century and, with titles like The Lonesome Trail and Other Stories, Gunman’s Reckoning, The Last of the Plainsmen, Way of the Lawlessand The Untamed, they are stereotypical of the romanticism of the frontier, the height of North American colonialism and a time when the indigenous population was being dispossessed of their lands and driven down to their lowest numbers in history as a direct result of European conflict, warfare and settlement.” The back cover describes the project:

Abel constructed the book’s source text by compiling ninety-one complete western novels found on the website Project Gutenberg, an online archive of public domain works. Using his word processor’s Ctrl-F function, he searched the document in its totality for words that relate to the political and social aspects of land, territory and ownership. Each search query represents a study in context (How was this word deployed? What surrounded it? What is left over once that word is removed?) that accumulates toward a representation of the public domain as a discoverable and inhabitable body of land.

There is something quite remarkable in the way that Abel, a Nisga’a writer from Vancouver, utilizes work that now exists in the public domain to reclaim and critique a representative and cultural space, using “conceptual writing [that] engages with the representation of Indigenous peoples in Anthropology through the technique of erasure.” Un/inhabited opens with erasure of specific words (uninhabited, settler, extracted, territory, indianized, pioneer, treaty, frontier, inhabited) before shifting to an erasure that shows the text almost as a cartographic map, before stripping the erasure down entirely, comparable to a depleting printer ink or photocopy toner cartridge. The only way these texts hold together is in the ways in which Abel allows them to degrade, before collapsing completely in on themselves. In an interview forthcoming at Touch the Donkey, he talks a bit about the compositional process of Un/inhabited:

After I finished writing Un/inhabited, there was a lot of material that essentially fell to the cutting room floor. I had been writing excessively, and knew that there would have to be substantial cuts for the project to be thematically coherent. As a result, there were many threads that had to be removed entirely. Some of those threads (minority, oil, afeared, etc.) were closely related to main conceptual project, but, for one reason or another, didn’t fit perfectly. Those threads were probably the most difficult to cut. Other threads (maps, speakers, urgency, etc.) were interesting explorations and worked individually, but were easy to separate from the main project. However, as the project continued, there were several threads that emerged that had coherent and discrete themes that weren’t dependent on the pieces in Un/inhabited. One of those threads explored the deployment of literary terms, and, surprisingly, seemed to be supported by the source text. That thread included many pieces: allegory, allusion, connotation, denouement, dialogue, flash back, hyperbole, identity, metaphor, motif, narrative, personification, simile, symbol, and theme.

To be honest, after I cut those pieces, I wasn’t really sure what to do with them. The pieces in Un/inhabited (settler, territory, frontier, etc.) worked partially because they explored themes of indigeneity, land use and ownership. Those pieces were actively working towards the destabilization of the colonial architecture of the western genre. But what were these other pieces doing? What did an exploration of the context surrounding the deployment of the word “allusion” accomplish?

I think, if I were to guess at an answer to my own question, that the thread of literary terms engages with an aspect of the western genre that is, at the very least, unusual. You don’t often think about the western genre being rich with metaphors or allusions or symbols, and, perhaps, it isn’t. But those words are there. Those words are doing something that we don’t normally associate with the traditional foundations of literary studies. There is an exploration here that, I think, subverts the tendencies of literary analysis by compressing and recontextualizing common analytic diction.

Right now, these pieces are not part of a separate project. But they easily could be. I think there’s more there to dig through. Other approaches that could be taken.

↧

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Yvonne Blomer

Yvonne Blomer’s most recent collection of poems is As if a Raven (Palimpsest Press, 2014). Her first book, a broken mirror, fallen leaf was short listed for the Gerald Lampert Memorial Award. Since 2009, Yvonne has been the Artistic Director of Planet Earth Poetry, a weekly reading series in Victoria, BC. In 2014 she became Victoria’s fourth Poet Laureate. www.yvonneblomer.com.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book came out in 2006, titled a broken mirror, fallen leaf. I got the first copies the day before my son was born, so my life changed with that book but in ways beyond the book.

a broken mirror, fallen leaf was shortlisted for the Gerald Lampert and I was utterly surprised by that, so in that way I think I gained something, perhaps encouragement or courage, because of that unexpected recognition.

Anyway, the book was my first, and one needs a first in order to get to the second and third which were piling up behind me.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Through an interest in the play of language over narrative or story. Narrative and story can also be in poetry, but language and line, metaphor, image and play are what drew and still draw me to poetry.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

My first and most recent books are contained either by place or theme, so they each provided a space within which I was writing. With my first book, I began writing as I was experiencing life in Japan through journaling. As if a Raven, my most recent book, started as my dissertation thesis, so I had to have a project, and I wanted a series of poems that were linked, but I didn’t know how they would be linked when I started.

As far as drafts of poems, anything is possible and they begin in a myriad of ways. Sometimes a poem in a first draft with few edits, sometimes notes, or the first few lines are on paper and I carry them around and build, sometimes the first few lines and I stall and return.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

My second book was made of poems that built over time and then I looked at them together and drew on common themes. As if a Raven was built over time as a book and I’m beginning a new project which is the same…it is a question or a series of questions so the writing that comes out will likely be linked. That said, there are always those free poems that just appear and they build into their own something.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I enjoy doing public readings and enjoy attending readings and lectures by writers. Readings provide food for thought, or fertilizer for future poems. Touring a book of poems and working on new writing at the same time is tricky to juggle. Even a five minute appearance at a festival takes a lot of energy to prepare for. I take it seriously, it is a performance, and part of the job so it takes focus, time and energy.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Yes, I do. I’m not sure what the current questions are but as a newly appointed Poet Laureate I’m concerned with how politics and poetry can merge and work for real change. Naively I want to use poetry to protect the Pacific Ocean. I think poetry is not simply image but image married to idea. The poet is concerned with/obsessed with/ has a question about something that leads to the images. Those images lead back to the concern or question and hopefully to some thought, an opening of thought and understanding in the writer and reader.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

This question carries on from the previous a little. I think a writer should draw attention to – a thought, idea, concern. A writer can open a door for readers. They also entertain, bring beauty, and bring attention to the moments of life.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Both. That engagement and back-and-forth on the poems or the order of the poems is vital to the end product and is part of the process. Engaging with an editor is another step in the process of making it as close to finished. It is often a deeper engagement because it is the last step in the process so there is more or a different kind of pressure on the writer, me, and the poems, to be their best.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Mark what you love in a poem with a highlighter and see what you have. I tend to mark what I don’t like. Focusing on what is working allows you to highlight the positive parts of the poem, even if it is just one line, and build from there. Also at Whistler Writers Festival last fall, Sue Goyette mentioned that she was allowing herself to take a break. It was superb to hear that. I was touring a lot and trying to write and feeling pretty worn out.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to creative non-fiction to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

I think it is not that easy. I feel like I bring poetry with me into nonfiction, which is fine, except sometimes I want to write a “true” essay, or in my mind I think I do, and then I begin writing and it leans toward the lyric. For many many years I’ve been working on a travel memoir, but not consistently until the last year and a half. I was letting myself get pulled to poetry projects and in order to finish this memoir, I needed to allow myself to refuse poetry for a while. Now as I’m getting closer to being finished, and beginning to write more poetry, I’m finding my lines are long and narrative so am trying to pull myself back toward the poetry. One way of helping to do this was I took a one day workshop on form poetry with Kate Braid offered through Wordstorm in Nanaimo. Just spending a day working on forms helped remind me of what I know, and push that different way of organizing my thoughts and words back to the foreground.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Well I have an 8 year old son. Once he’s at school, on an ideal day, I take a brisk walk around Cedar Hill Golf Course then head home to gather papers from the cluttered kitchen table and go out the back door to my studio. I stay there as long as I can, usually until 2 when I come back in to get ready to pick my son up. At some point between 10-2 I nip in for tea and a bowl of random snacks to crunch on. Crunchy food is good for writing (so says fiction writer Julie Paul).

On a more typical day, with Planet Earth Poetry and Poet Laureate duties there is a fair amount of emailing between gathering papers and laptop and getting out to the studio (where the wifi is weak).

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

A walk helps. Jumping around on-line further stalls me and shuts down the thinking self. Reading poems by Steven Price, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Meira Cook, Cornelia Hoogland, Iliya Kaminsky etc…helps too. Picking up a magazine like The Malahat, Arc, TNQ is always great to inspire.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Rain, earth, light fragrance of cherry blossoms/magnolia (spring in Victoria) The damp air.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Everything influences my work. A question. Students’ work. Prompts I give to students and their responses sometimes open a response in me. Books I’m reading. A passage or an entire book, for its tone or how the author approaches the subject. I feel like I’m a composting worm...I take anything and everything. Who knows where it might reappear years or days or minutes from now. I think that is part of the process. Art, science, a word, a walk, an animal (my dog), a scent.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I love reading fiction, mysteries, really good fiction, anything (even vampire stories) before bed. During the day I read nonfiction and poetry. I sometimes read poetry before bed, but it often over-stimulates me. A powerful nonfiction novel can be just as good as a book of fiction, but I love sinking into a novel. Right now I’m reading Late Nights on Air by Elizabeth Hay, which is set in the Northwest Territories. I started it in the Yukon (when I was up there reading), so I have partly stayed north due to reading it. It is a wonderful story with sublime descriptions and a creepy/unsettled feeling throughout.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Work in translation. French and Japanese. Have my poems translated. Finish my travel memoir.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Spy. Well, I doubt I would have been a great spy. Maybe a bicycle tour operator. When I first moved home from Japan I was beginning to start a cycling company called Pacific Pedals. My sister reminded me and encouraged me to keep at the writing, so I did.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

That is a tough one to answer. I’ve always loved writing, communicating with myself in the written word. I think that love lead to a desire to communicate in a larger way. I started with journalism courses at College and then took poetry with Patrick Lane at the University of Victoria a fair while ago. He scared me. Fear and passion are cousins to nerves and excitement.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Boundless by Kathleen Winter, Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf and Wild by Cheryl Strayed.

I loved the film version of Wild, as well as The Lunch Box. I also loved Paddington my son’s new favourite.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Did I mention a memoir?

I am beginning a new project and ending (hopefully) an old one. I have been (re)reading Virginia Woolf and Gwendolyn MacEwen and reading about Janis Joplin. I watched part of the Downton Abbey series and began to wonder how we went from Pre-WWI and how women’s lives looked to creating Virginia Woolf and how we got to Joplin in the 1960s and where MacEwen and her genius came from and how it fits in. So I’m exploring female artists and how one led to the next and whether society can or does support genius in women. I’m doing this in poetry or lyric prose. I kind of hate to say I’m doing it as I’m so so so at the beginning. Truthfully, I’m reading a lot.

And I’m finishing a memoir set in Southeast Asia where my husband and I cycled for three months from Vietnam through Laos, Thailand and on to Malaysia.

And I’m a new Poet Laureate with Poetry Month fast approaching so feel more like an arts organizer (plus PEP) than a writer many days. I think that balance between writing time and planning events will get easier (I hope).

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book came out in 2006, titled a broken mirror, fallen leaf. I got the first copies the day before my son was born, so my life changed with that book but in ways beyond the book.

a broken mirror, fallen leaf was shortlisted for the Gerald Lampert and I was utterly surprised by that, so in that way I think I gained something, perhaps encouragement or courage, because of that unexpected recognition.

Anyway, the book was my first, and one needs a first in order to get to the second and third which were piling up behind me.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Through an interest in the play of language over narrative or story. Narrative and story can also be in poetry, but language and line, metaphor, image and play are what drew and still draw me to poetry.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

My first and most recent books are contained either by place or theme, so they each provided a space within which I was writing. With my first book, I began writing as I was experiencing life in Japan through journaling. As if a Raven, my most recent book, started as my dissertation thesis, so I had to have a project, and I wanted a series of poems that were linked, but I didn’t know how they would be linked when I started.

As far as drafts of poems, anything is possible and they begin in a myriad of ways. Sometimes a poem in a first draft with few edits, sometimes notes, or the first few lines are on paper and I carry them around and build, sometimes the first few lines and I stall and return.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

My second book was made of poems that built over time and then I looked at them together and drew on common themes. As if a Raven was built over time as a book and I’m beginning a new project which is the same…it is a question or a series of questions so the writing that comes out will likely be linked. That said, there are always those free poems that just appear and they build into their own something.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I enjoy doing public readings and enjoy attending readings and lectures by writers. Readings provide food for thought, or fertilizer for future poems. Touring a book of poems and working on new writing at the same time is tricky to juggle. Even a five minute appearance at a festival takes a lot of energy to prepare for. I take it seriously, it is a performance, and part of the job so it takes focus, time and energy.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Yes, I do. I’m not sure what the current questions are but as a newly appointed Poet Laureate I’m concerned with how politics and poetry can merge and work for real change. Naively I want to use poetry to protect the Pacific Ocean. I think poetry is not simply image but image married to idea. The poet is concerned with/obsessed with/ has a question about something that leads to the images. Those images lead back to the concern or question and hopefully to some thought, an opening of thought and understanding in the writer and reader.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

This question carries on from the previous a little. I think a writer should draw attention to – a thought, idea, concern. A writer can open a door for readers. They also entertain, bring beauty, and bring attention to the moments of life.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Both. That engagement and back-and-forth on the poems or the order of the poems is vital to the end product and is part of the process. Engaging with an editor is another step in the process of making it as close to finished. It is often a deeper engagement because it is the last step in the process so there is more or a different kind of pressure on the writer, me, and the poems, to be their best.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Mark what you love in a poem with a highlighter and see what you have. I tend to mark what I don’t like. Focusing on what is working allows you to highlight the positive parts of the poem, even if it is just one line, and build from there. Also at Whistler Writers Festival last fall, Sue Goyette mentioned that she was allowing herself to take a break. It was superb to hear that. I was touring a lot and trying to write and feeling pretty worn out.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to creative non-fiction to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

I think it is not that easy. I feel like I bring poetry with me into nonfiction, which is fine, except sometimes I want to write a “true” essay, or in my mind I think I do, and then I begin writing and it leans toward the lyric. For many many years I’ve been working on a travel memoir, but not consistently until the last year and a half. I was letting myself get pulled to poetry projects and in order to finish this memoir, I needed to allow myself to refuse poetry for a while. Now as I’m getting closer to being finished, and beginning to write more poetry, I’m finding my lines are long and narrative so am trying to pull myself back toward the poetry. One way of helping to do this was I took a one day workshop on form poetry with Kate Braid offered through Wordstorm in Nanaimo. Just spending a day working on forms helped remind me of what I know, and push that different way of organizing my thoughts and words back to the foreground.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?